Exploring Fully Homomorphic Encryption

2020 Jul 20

See all posts

Exploring Fully Homomorphic Encryption

Special thanks to Karl Floersch and Dankrad Feist for

review

Fully homomorphic encryption has for a long time been considered one

of the holy grails of cryptography. The promise of fully homomorphic

encryption (FHE) is powerful: it is a type of encryption that allows a

third party to perform computations on encrypted data, and get an

encrypted result that they can hand back to whoever has the decryption

key for the original data, without the third party being able

to decrypt the data or the result themselves.

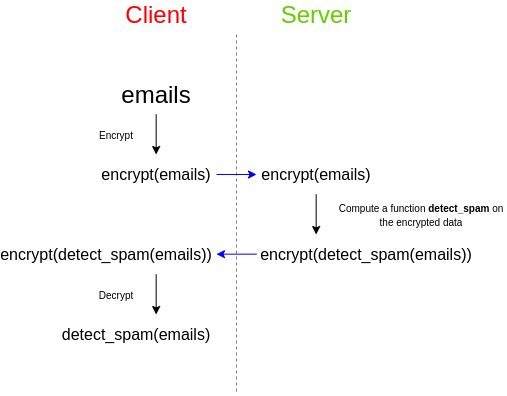

As a simple example, imagine that you have a set of emails, and you

want to use a third party spam filter to check whether or not they are

spam. The spam filter has a desire for privacy of their

algorithm: either the spam filter provider wants to keep their

source code closed, or the spam filter depends on a very large database

that they do not want to reveal publicly as that would make attacking

easier, or both. However, you care about the privacy of your

data, and don't want to upload your unencrypted emails to a third

party. So here's how you do it:

Fully homomorphic encryption has many applications, including in the

blockchain space. One key example is that can be used to implement

privacy-preserving light clients (the light client hands the server an

encrypted index i, the server computes and returns

data[0] * (i = 0) + data[1] * (i = 1) + ... + data[n] * (i = n),

where data[i] is the i'th piece of data in a block or state

along with its Merkle branch and (i = k) is an expression

that returns 1 if i = k and otherwise 0; the light client

gets the data it needs and the server learns nothing about what the

light client asked).

It can also be used for:

- More efficient stealth

address protocols, and more generally scalability solutions to

privacy-preserving protocols that today require each user to personally

scan the entire blockchain for incoming transactions

- Privacy-preserving data-sharing marketplaces that let users allow

some specific computation to be performed on their data while keeping

full control of their data for themselves

- An ingredient in more powerful cryptographic primitives, such as

more efficient multi-party computation protocols and perhaps eventually

obfuscation

And it turns out that fully homomorphic encryption is, conceptually,

not that difficult to understand!

Partially,

Somewhat, Fully homomorphic encryption

First, a note on definitions. There are different kinds of

homomorphic encryption, some more powerful than others, and they are

separated by what kinds of functions one can compute on the encrypted

data.

- Partially homomorphic encryption allows evaluating

only a very limited set of operations on encrypted data: either

just additions (so given

encrypt(a) and

encrypt(b) you can compute encrypt(a+b)), or

just multiplications (given encrypt(a) and

encrypt(b) you can compute encrypt(a*b)).

- Somewhat homomorphic encryption allows computing

additions as well as a limited number of multiplications

(alternatively, polynomials up to a limited degree). That is, if you get

encrypt(x1) ... encrypt(xn) (assuming these are "original"

encryptions and not already the result of homomorphic computation), you

can compute encrypt(p(x1 ... xn)), as long as

p(x1 ... xn) is a polynomial with degree

< D for some specific degree bound D

(D is usually very low, think 5-15).

- Fully homomorphic encryption allows unlimited

additions and multiplications. Additions and multiplications let you

replicate any binary circuit gates (

AND(x, y) = x*y,

OR(x, y) = x+y-x*y, XOR(x, y) = x+y-2*x*y or

just x+y if you only care about even vs odd,

NOT(x) = 1-x...), so this is sufficient to do arbitrary

computation on encrypted data.

Partially homomorphic encryption is fairly easy; eg. RSA has a

multiplicative homomorphism: \(enc(x) =

x^e\), \(enc(y) = y^e\), so

\(enc(x) * enc(y) = (xy)^e = enc(xy)\).

Elliptic curves can offer similar properties with addition. Allowing

both addition and multiplication is, it turns out,

significantly harder.

A simple somewhat-HE

algorithm

Here, we will go through a somewhat-homomorphic encryption algorithm

(ie. one that supports a limited number of multiplications) that is

surprisingly simple. A more complex version of this category of

technique was used by Craig Gentry to create the first-ever

fully homomorphic scheme in 2009. More recent efforts have

switched to using different schemes based on vectors and matrices, but

we will still go through this technique first.

We will describe all of these encryption schemes as

secret-key schemes; that is, the same key is used to encrypt

and decrypt. Any secret-key HE scheme can be turned into a public key

scheme easily: a "public key" is typically just a set of many

encryptions of zero, as well as an encryption of one (and possibly more

powers of two). To encrypt a value, generate it by adding together the

appropriate subset of the non-zero encryptions, and then adding a random

subset of the encryptions of zero to "randomize" the ciphertext and make

it infeasible to tell what it represents.

The secret key here is a large prime, \(p\) (think of \(p\) as having hundreds or even thousands of

digits). The scheme can only encrypt 0 or 1, and "addition" becomes XOR,

ie. 1 + 1 = 0. To encrypt a value \(m\)

(which is either 0 or 1), generate a large random value \(R\) (this will typically be even larger

than \(p\)) and a smaller random value

\(r\) (typically much smaller than

\(p\)), and output:

\[enc(m) = R * p + r * 2 + m\]

To decrypt a ciphertext \(ct\),

compute:

\[dec(ct) = (ct\ mod\ p)\ mod\

2\]

To add two ciphertexts \(ct_1\) and

\(ct_2\), you simply, well, add them:

\(ct_1 + ct_2\). And to multiply two

ciphertexts, you once again... multiply them: \(ct_1 * ct_2\). We can prove the homomorphic

property (that the sum of the encryptions is an encryption of the sum,

and likewise for products) as follows.

Let:

\[ct_1 = R_1 * p + r_1 * 2 + m_1\]

\[ct_2 = R_2 * p + r_2 * 2 + m_2\]

We add:

\[ct_1 + ct_2 = R_1 * p + R_2 * p + r_1 *

2 + r_2 * 2 + m_1 + m_2\]

Which can be rewritten as:

\[(R_1 + R_2) * p + (r_1 + r_2) * 2 + (m_1

+ m_2)\]

Which is of the exact same "form" as a ciphertext of \(m_1 + m_2\). If you decrypt it, the first

\(mod\ p\) removes the first term, the

second \(mod\ 2\) removes the second

term, and what's left is \(m_1 + m_2\)

(remember that if \(m_1 = 1\) and \(m_2 = 1\) then the 2 will get absorbed into

the second term and you'll be left with zero). And so, voila, we have

additive homomorphism!

Now let's check multiplication:

\[ct_1 * ct_2 = (R_1 * p + r_1 * 2 + m_1)

* (R_2 * p + r_2 * 2 + m_2)\]

Or:

\[(R_1 * R_2 * p + r_1 * 2 + m_1 + r_2 * 2

+ m_2) * p + \] \[(r_1 * r_2 * 2 + r_1

* m_2 + r_2 * m_1) * 2 + \] \[(m_1 *

m_2)\]

This was simply a matter of expanding the product above, and grouping

together all the terms that contain \(p\), then all the remaining terms that

contain \(2\), and finally the

remaining term which is the product of the messages. If you decrypt,

then once again the \(mod\ p\) removes

the first group, the \(mod\ 2\) removes

the second group, and only \(m_1 *

m_2\) is left.

But there are two problems here: first, the size of the ciphertext

itself grows (the length roughly doubles when you multiply), and second,

the "noise" (also often called "error") in the smaller \(\* 2\) term also gets quadratically bigger.

Adding this error into the ciphertexts was necessary because the

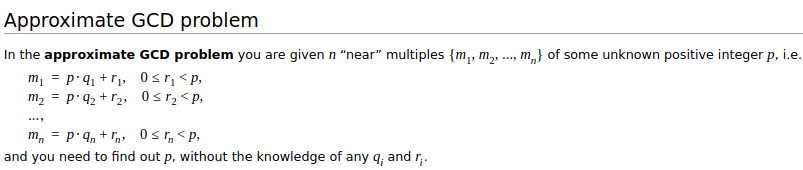

security of this scheme is based on the approximate

GCD problem:

Had we instead used the "exact GCD problem", breaking the system

would be easy: if you just had a set of expressions of the form \(p * R_1 + m_1\), \(p * R_2 + m_2\)..., then you could use the Euclidean

algorithm to efficiently compute the greatest common divisor \(p\). But if the ciphertexts are only

approximate multiples of \(p\)

with some "error", then extracting \(p\) quickly becomes impractical, and so the

scheme can be secure.

Unfortunately, the error introduces the inherent limitation that if

you multiply the ciphertexts by each other enough times, the error

eventually grows big enough that it exceeds \(p\), and at that point the \(mod\ p\) and \(mod\ 2\) steps "interfere" with each other,

making the data unextractable. This will be an inherent tradeoff in all

of these homomorphic encryption schemes: extracting information from

approximate equations "with errors" is much harder than

extracting information from exact equations, but any error you add

quickly increases as you do computations on encrypted data, bounding the

amount of computation that you can do before the error becomes

overwhelming. And this is why these schemes are only "somewhat"

homomorphic.

Bootstrapping

There are two classes of solution to this problem. First, in many

somewhat homomorphic encryption schemes, there are clever tricks to make

multiplication only increase the error by a constant factor (eg. 1000x)

instead of squaring it. Increasing the error by 1000x still sounds by a

lot, but keep in mind that if \(p\) (or

its equivalent in other schemes) is a 300-digit number, that means that

you can multiply numbers by each other 100 times, which is enough to

compute a very wide class of computations. Second, there is Craig

Gentry's technique of "bootstrapping".

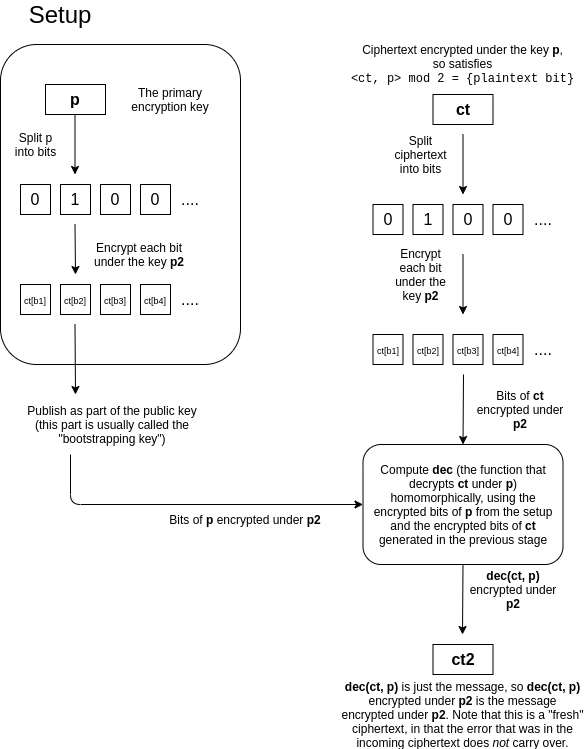

Suppose that you have a ciphertext \(ct\) that is an encryption of some \(m\) under a key \(p\), that has a lot of error. The idea is

that we "refresh" the ciphertext by turning it into a new ciphertext of

\(m\) under another key \(p_2\), where this process "clears out" the

old error (though it will introduce a fixed amount of new error). The

trick is quite clever. The holder of \(p\) and \(p_2\) provides a "bootstrapping key" that

consists of an encryption of the bits of \(p\) under the key \(p_2\), as well as the public key for \(p_2\). Whoever is doing computations on

data encrypted under \(p\) would then

take the bits of the ciphertext \(ct\),

and individually encrypt these bits under \(p_2\). They would then homomorphically

compute the decryption under \(p\)

using these ciphertexts, and get out the single bit, which would be

\(m\) encrypted under \(p_2\).

This is difficult to understand, so we can restate it as follows. The

decryption procedure \(dec(ct, p)\)

is itself a computation, and so it can itself be

implemented as a circuit that takes as input the bits of \(ct\) and the bits of \(p\), and outputs the decrypted bit \(m \in {0, 1}\). If someone has a ciphertext

\(ct\) encrypted under \(p\), a public key for \(p_2\), and the bits of \(p\) encrypted under \(p_2\), then they can compute \(dec(ct, p) = m\) "homomorphically", and get

out \(m\) encrypted under \(p_2\). Notice that the decryption procedure

itself washes away the old error; it just outputs 0 or 1. The decryption

procedure is itself a circuit, which contains additions or

multiplications, so it will introduce new error, but this new error

does not depend on the amount of error in the original

encryption.

(Note that we can avoid having a distinct new key \(p_2\) (and if you want to bootstrap

multiple times, also a \(p_3\), \(p_4\)...) by just setting \(p_2 = p\). However, this introduces a new

assumption, usually called "circular security"; it becomes

more difficult to formally prove security if you do this, though

many cryptographers think it's fine and circular security poses no

significant risk in practice)

But.... there is a catch. In the scheme as described above (using

circular security or not), the error blows up so quickly that even the

decryption circuit of the scheme itself is too much for it. That is, the

new \(m\) encrypted under \(p_2\) would already have so much

error that it is unreadable. This is because each AND gate doubles the

bit-length of the error, so a scheme using a \(d\)-bit modulus \(p\) can only handle less than \(log(d)\) multiplications (in series), but

decryption requires computing \(mod\

p\) in a circuit made up of these binary logic gates, which

requires... more than \(log(d)\)

multiplications.

Craig Gentry came up with clever techniques to get around this

problem, but they are arguably too complicated to explain; instead, we

will skip straight to newer work from 2011 and 2013, that solves this

problem in a different way.

Learning with errors

To move further, we will introduce a different type of

somewhat-homomorphic encryption introduced by Brakerski and

Vaikuntanathan in 2011, and show how to bootstrap it. Here, we will move

away from keys and ciphertexts being integers, and instead have

keys and ciphertexts be vectors. Given a key \(k = {k_1, k_2 .... k_n}\), to encrypt a

message \(m\), construct a vector \(c = {c_1, c_2 ... c_n}\) such that the

inner product (or "dot product") \(<c, k> = c_1k_1 + c_2k_1 + ... +

c_nk_n\), modulo some fixed number \(p\), equals \(m+2e\) where \(m\) is the message (which must be 0 or 1),

and \(e\) is a small (much smaller than

\(p\)) "error" term. A "public key"

that allows encryption but not decryption can be constructed, as before,

by making a set of encryptions of 0; an encryptor can randomly combine a

subset of these equations and add 1 if the message they are encrypting

is 1. To decrypt a ciphertext \(c\)

knowing the key \(k\), you would

compute \(<c, k>\) modulo \(p\), and see if the result is odd or even

(this is the same "mod p mod 2" trick we used earlier). Note that here

the \(mod\ p\) is typically a

"symmetric" mod, that is, it returns a number between \(-\frac{p}{2}\) and \(\frac{p}{2}\) (eg. 137 mod 10 = -3, 212 mod

10 = 2); this allows our error to be positive or negative. Additionally,

\(p\) does not necessarily have to be

prime, though it does need to be odd.

|

Key

|

3

|

14

|

15

|

92

|

65

|

|

Ciphertext

|

2

|

71

|

82

|

81

|

8

|

The key and the ciphertext are both vectors, in this example

of five elements each.

In this example, we set the modulus \(p =

103\). The dot product is

3 * 2 + 14 * 71 + 15 * 82 + 92 * 81 + 65 * 8 = 10202, and

\(10202 = 99 * 103 + 5\). 5 itself is

of course \(2 * 2 + 1\), so the message

is 1. Note that in practice, the first element of the key is often set

to \(1\); this makes it easier to

generate ciphertexts for a particular value (see if you can figure out

why).

The security of the scheme is based on an assumption known as "learning with

errors" (LWE) - or, in more jargony but also more understandable

terms, the hardness of solving systems of equations with

errors.

A ciphertext can itself be viewed as an equation: \(k_1c_1 + .... + k_nc_n \approx 0\), where

the key \(k_1 ... k_n\) is the

unknowns, the ciphertext \(c_1 ...

c_n\) is the coefficients, and the equality is only approximate

because of both the message (0 or 1) and the error (\(2e\) for some relatively small \(e\)). The LWE assumption ensures that even

if you have access to many of these ciphertexts, you cannot recover

\(k\).

Note that in some descriptions of LWE, <c, k> can

equal any value, but this value must be provided as part of the

ciphertext. This is mathematically equivalent to the <c, k> = m+2e

formulation, because you can just add this answer to the end of the

ciphertext and add -1 to the end of the key, and get two vectors that

when multiplied together just give m+2e. We'll use the formulation that

requires <c, k> to be near-zero (ie. just m+2e) because it is

simpler to work with.

Multiplying ciphertexts

It is easy to verify that the encryption is additive: if \(<ct_1, k> = 2e_1 + m_1\) and \(<ct_2, k> = 2e_2 + m_2\), then \(<ct_1 + ct_2, k> = 2(e_1 + e_2) + m_1 +

m_2\) (the addition here is modulo \(p\)). What is harder is multiplication:

unlike with numbers, there is no natural way to multiply two length-n

vectors into another length-n vector. The best that we can do is the outer product: a

vector containing the products of each possible pair where the first

element comes from the first vector and the second element comes from

the second vector. That is, \(a \otimes b =

a_1b_1 + a_2b_1 + ... + a_nb_1 + a_1b_2 + ... + a_nb_2 + ... +

a_nb_n\). We can "multiply ciphertexts" using the convenient

mathematical identity \(<a \otimes b, c

\otimes d> = <a, c> * <b, d>\).

Given two ciphertexts \(c_1\) and

\(c_2\), we compute the outer product

\(c_1 \otimes c_2\). If both \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) were encrypted with \(k\), then \(<c_1, k> = 2e_1 + m_1\) and \(<c_2, k> = 2e_2 + m_2\). The outer

product \(c_1 \otimes c_2\) can be

viewed as an encryption of \(m_1 *

m_2\) under \(k \otimes k\); we

can see this by looking what happens when we try to decrypt with \(k \otimes k\):

\[<c_1 \otimes c_2, k \otimes

k>\] \[= <c_1, k> * <c_2,

k>\] \[ = (2e_1 + m_1) * (2e_2 +

m_2)\] \[ = 2(e_1m_2 + e_2m_1 +

2e_1e_2) + m_1m_2\]

So this outer-product approach works. But there is, as you may have

already noticed, a catch: the size of the ciphertext, and the key, grows

quadratically.

Relinearization

We solve this with a relinearization procedure. The

holder of the private key \(k\)

provides, as part of the public key, a "relinearization key", which you

can think of as "noisy" encryptions of \(k

\otimes k\) under \(k\). The

idea is that we provide these encrypted pieces of \(k \otimes k\) to anyone performing the

computations, allowing them to compute the equation \(<c_1 \otimes c_2, k \otimes k>\) to

"decrypt" the ciphertext, but only in such a way that the output comes

back encrypted under \(k\).

It's important to understand what we mean here by "noisy

encryptions". Normally, this encryption scheme only allows encrypting

\(m \in \{0,1\}\), and an "encryption

of \(m\)" is a vector \(c\) such that \(<c, k> = m+2e\) for some small error

\(e\). Here, we're "encrypting"

arbitrary \(m \in \{0,1, 2....p-1\}\).

Note that the error means that you can't fully recover \(m\) from \(c\); your answer will be off by some

multiple of 2. However, it turns out that, for this specific use case,

this is fine.

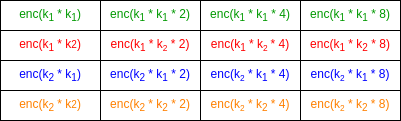

The relinearization key consists of a set of vectors which, when

inner-producted (modulo \(p\)) with the

key \(k\), give values of the form

\(k_i * k_j * 2^d + 2e\) (mod \(p\)), one such vector for every possible

triple \((i, j, d)\), where \(i\) and \(j\) are indices in the key and \(d\) is an exponent where \(2^d < p\) (note: if the key has length

\(n\), there would be \(n^2 * log(p)\) values in the

relinearization key; make sure you understand why before

continuing).

Example assuming p = 15 and k has length 2. Formally, enc(x)

here means "outputs x+2e if inner-producted with k".

Now, let us take a step back and look again at our goal. We have a

ciphertext which, if decrypted with \(k

\otimes k\), gives \(m_1 *

m_2\). We want a ciphertext which, if decrypted with

\(k\), gives \(m_1 * m_2\). We can do this with the

relinearization key. Notice that the decryption equation \(<ct_1 \otimes ct_2, k \otimes k>\) is

just a big sum of terms of the form \((ct_{1_i} * ct_{2_j}) * k_p * k_q\).

And what do we have in our relinearization key? A bunch of elements

of the form \(2^d * k_p * k_q\),

noisy-encrypted under \(k\), for every

possible combination of \(p\) and \(q\)! Having all the powers of two in our

relinearization key allows us to generate any \((ct_{1_i} * ct_{2_j}) * k_p * k_q\) by just

adding up \(\le log(p)\) powers of two

(eg. 13 = 8 + 4 + 1) together for each \((p,

q)\) pair.

For example, if \(ct_1 = [1, 2]\)

and \(ct_2 = [3, 4]\), then \(ct_1 \otimes ct_2 = [3, 4, 6, 8]\), and

\(enc(<ct_1 \otimes ct_2, k \otimes k>)

= enc(3k_1k_1 + 4k_1k_2 + 6k_2k_1 + 8k_2k_2)\) could be computed

via:

\[enc(k_1 * k_1) + enc(k_1 * k_1 * 2) +

enc(k_1 * k_2 * 4) + \]

\[enc(k_2 * k_1 * 2) + enc(k_2 * k_1 *

4) + enc(k_2 * k_2 * 8) \]

Note that each noisy-encryption in the relinearization key has some

even error \(2e\), and the equation

\(<ct_1 \otimes ct_2, k \otimes

k>\) itself has some error: if \(<ct_1, k> = 2e_1 + m_1\) and \(<ct_2 + k> = 2e_2 + m_2\), then \(<ct_1 \otimes ct_2, k \otimes k> =\)

\(<ct_1, k> * <ct_2 + k>

=\) \(2(2e_1e_2 + e_1m_2 + e_2m_1) +

m_1m_2\). But this total error is still (relatively) small (\(2e_1e_2 + e_1m_2 + e_2m_1\) plus \(n^2 * log(p)\) fixed-size errors from the

realinearization key), and the error is even, and so the result of this

calculation still gives a value which, when inner-producted with \(k\), gives \(m_1

* m_2 + 2e'\) for some "combined error" \(e'\).

The broader technique we used here is a common trick in homomorphic

encryption: provide pieces of the key encrypted under the key itself (or

a different key if you are pedantic about avoiding circular security

assumptions), such that someone computing on the data can compute the

decryption equation, but only in such a way that the output itself is

still encrypted. It was used in bootstrapping above, and it's used here;

it's best to make sure you mentally understand what's going on in both

cases.

This new ciphertext has considerably more error in it: the \(n^2 * log(p)\) different errors from the

portions of the relinearization key that we used, plus the \(2(2e_1e_2 + e_1m_2 + e_2m_1)\) from the

original outer-product ciphertext. Hence, the new ciphertext still does

have quadratically larger error than the original ciphertexts, and so we

still haven't solved the problem that the error blows up too quickly. To

solve this, we move on to another trick...

Modulus switching

Here, we need to understand an important algebraic fact. A ciphertext

is a vector \(ct\), such that \(<ct, k> = m+2e\), where \(m \in \{0,1\}\). But we can also look at

the ciphertext from a different "perspective": consider \(\frac{ct}{2}\) (modulo \(p\)). \(<\frac{ct}{2}, k> = \frac{m}{2} +

e\), where \(\frac{m}{2} \in

\{0,\frac{p+1}{2}\}\). Note that because (modulo \(p\)) \((\frac{p+1}{2})*2 = p+1 = 1\), division by

2 (modulo \(p\)) maps \(1\) to \(\frac{p+1}{2}\); this is a very convenient

fact for us.

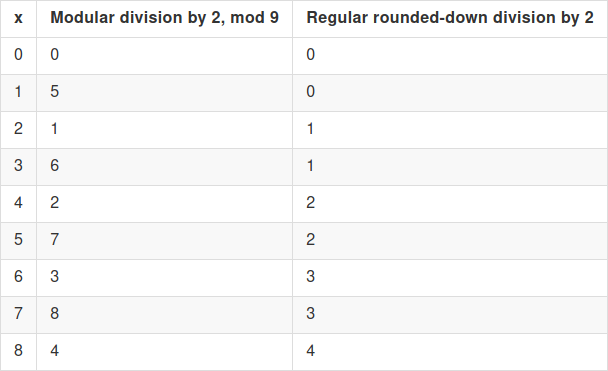

The scheme in this section uses both modular division (ie.

multiplying by the modular

multiplicative inverse) and regular "rounded down" integer division;

make sure you understand how both work and how they are different from

each other.

That is, the operation of dividing by 2 (modulo \(p\)) converts small even numbers into small

numbers, and it converts 1 into \(\frac{p}{2}\) (rounded up). So if we look

at \(\frac{ct}{2}\) (modulo \(p\)) instead of \(ct\), decryption involves computing \(<\frac{ct}{2}, k>\) and seeing if

it's closer to \(0\) or \(\frac{p}{2}\). This "perspective" is much

more robust to certain kinds of errors, where you know the error is

small but can't guarantee that it's a multiple of 2.

Now, here is something we can do to a ciphertext.

- Start: \(<ct, k> = \{0\ or\ 1\} +

2e\ (mod\ p)\)

- Divide \(ct\) by 2 (modulo \(p\)): \(<ct', k> = \{0\ or\ \frac{p}{2}\} + e\

(mod\ p)\)

- Multiply \(ct'\) by \(\frac{q}{p}\) using "regular

rounded-down integer division": \(<ct'', k> = \{0\ or\ \frac{q}{2}\} +

e' + e_2\ (mod\ q)\)

- Multiply \(ct''\) by 2

(modulo \(q\)): \(<ct''', k> = \{0\ or\ 1\} +

2e' + 2e_2\ (mod\ q)\)

Step 3 is the crucial one: it converts a ciphertext under modulus

\(p\) into a ciphertext under modulus

\(q\). The process just involves

"scaling down" each element of \(ct'\) by multiplying by \(\frac{q}{p}\) and rounding down, eg. \(floor(56 * \frac{15}{103}) = floor(8.15533..) =

8\).

The idea is this: if \(<ct', k> =

m*\frac{p}{2} + e\ (mod\ p)\), then we can interpret this as

\(<ct', k> = p(z + \frac{m}{2}) +

e\) for some integer \(z\).

Therefore, \(<ct' * \frac{q}{p}, k>

= q(z + \frac{m}{2}) + e*\frac{p}{q}\). Rounding adds error, but

only a little bit (specifically, up to the size of the values in \(k\), and we can make the values in \(k\) small without sacrificing security).

Therefore, we can say \(<ct' *

\frac{q}{p}, k> = m*\frac{q}{2} + e' + e_2\ (mod\ q)\),

where \(e' = e * \frac{q}{p}\), and

\(e_2\) is a small error from

rounding.

What have we accomplished? We turned a ciphertext with modulus \(p\) and error \(2e\) into a ciphertext with modulus \(q\) and error \(2(floor(e*\frac{p}{q}) + e_2)\), where the

new error is smaller than the original error.

Let's go through the above with an example. Suppose:

- \(ct\) is just one value, \([5612]\)

- \(k = [9]\)

- \(p = 9999\) and \(q = 113\)

\(<ct, k> = 5612 * 9 = 50508 = 9999 *

5 + 2 * 256 + 1\), so \(ct\)

represents the bit 1, but the error is fairly large (\(e = 256\)).

Step 2: \(ct' = \frac{ct}{2} =

2806\) (remember this is modular division; if \(ct\) were instead \(5613\), then we would have \(\frac{ct}{2} = 7806\)). Checking: \(<ct', k> = 2806 * 9 = 25254 = 9999 * 2.5

+ 256.5\)

Step 3: \(ct'' = floor(2806 *

\frac{113}{9999}) = floor(31.7109...) = 31\). Checking: \(<ct'', k> = 279 = 113 * 2.5 -

3.5\)

Step 4: \(ct''' = 31 * 2 =

62\). Checking: \(<ct''', k> = 558 = 113 * 5 - 2 *

4 + 1\)

And so the bit \(1\) is preserved

through the transformation. The crazy thing about this procedure is:

none of it requires knowing \(k\). Now, an astute reader might

notice: you reduced the absolute size of the error (from 256 to

2), but the relative size of the error remained unchanged, and

even slightly increased: \(\frac{256}{9999}

\approx 2.5\%\) but \(\frac{4}{113}

\approx 3.5\%\). Given that it's the relative error that causes

ciphertexts to break, what have we gained here?

The answer comes from what happens to error when you multiply

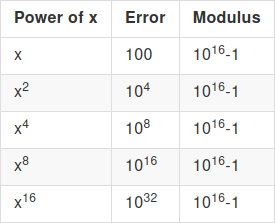

ciphertexts. Suppose that we start with a ciphertext \(x\) with error 100, and modulus \(p = 10^{16} - 1\). We want to repeatedly

square \(x\), to compute \((((x^2)^2)^2)^2 = x^{16}\). First, the

"normal way":

The error blows up too quickly for the computation to be possible.

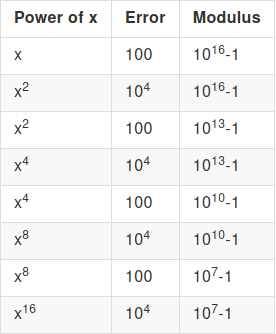

Now, let's do a modulus reduction after every multiplication. We assume

the modulus reduction is imperfect and increases error by a factor of

10, so a 1000x modulo reduction only reduces error from 10000 to 100

(and not to 10):

The key mathematical idea here is that the factor by which

error increases in a multiplication depends on the absolute size of the

error, and not its relative size, and so if we keep doing modulus

reductions to keep the error small, each multiplication only increases

the error by a constant factor. And so, with a \(d\) bit modulus (and hence \(\approx 2^d\) room for "error"), we can do

\(O(d)\) multiplications! This is

enough to bootstrap.

Another technique: matrices

Another technique (see Gentry, Sahai, Waters

(2013)) for fully homomorphic encryption involves matrices: instead

of representing a ciphertext as \(ct\)

where \(<ct, k> = 2e + m\), a

ciphertext is a matrix, where \(k * CT = k * m

+ e\) (\(k\), the key, is still

a vector). The idea here is that \(k\)

is a "secret near-eigenvector" - a secret vector which, if you multiply

the matrix by it, returns something very close to either zero or the key

itself.

The fact that addition works is easy: if \(k * CT_1 = m_1 * k + e_1\) and \(k * CT_2 = m_2 * k + e_2\), then \(k * (CT_1 + CT_2) = (m_1 + m_2) * k + (e_1 +

e_2)\). The fact that multiplication works is also easy:

\(k * CT_1 * CT_2\) \(= (m_1 * k + e_1) * CT_2\) \(= m_1 * k * CT_2 + e_1 * CT_2\) \(= m_1 * m_2 * k + m_1 * e_2 + e_1 *

CT_2\)

The first term is the "intended term"; the latter two terms are the

"error". That said, notice that here error does blow up quadratically

(see the \(e_1 * CT_2\) term; the size

of the error increases by the size of each ciphertext element, and the

ciphertext elements also square in size), and you do need some clever

tricks for avoiding this. Basically, this involves turning ciphertexts

into matrices containing their constituent bits before multiplying, to

avoid multiplying by anything higher than 1; if you want to see how this

works in detail I recommend looking at my code: https://github.com/vbuterin/research/blob/master/matrix_fhe/matrix_fhe.py#L121

In addition, the code there, and also https://github.com/vbuterin/research/blob/master/tensor_fhe/homomorphic_encryption.py#L186,

provides simple examples of useful circuits that you can build out of

these binary logical operations; the main example is for adding numbers

that are represented as multiple bits, but one can also make circuits

for comparison (\(<\), \(>\), \(=\)), multiplication, division, and many

other operations.

Since 2012-13, when these algorithms were created, there have been

many optimizations, but they all work on top of these basic frameworks.

Often, polynomials are used instead of integers; this is called ring

LWE. The major challenge is still efficiency: an operation involving

a single bit involves multiplying entire matrices or performing an

entire relinearization computation, a very high overhead. There are

tricks that allow you to perform many bit operations in a single

ciphertext operation, and this is actively being worked on and

improved.

We are quickly getting to the point where many of the applications of

homomorphic encryption in privacy-preserving computation are starting to

become practical. Additionally, research in the more advanced

applications of the lattice-based cryptography used in homomorphic

encryption is rapidly progressing. So this is a space where some things

can already be done today, but we can hopefully look forward to much

more becoming possible over the next decade.

Exploring Fully Homomorphic Encryption

2020 Jul 20 See all postsSpecial thanks to Karl Floersch and Dankrad Feist for review

Fully homomorphic encryption has for a long time been considered one of the holy grails of cryptography. The promise of fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) is powerful: it is a type of encryption that allows a third party to perform computations on encrypted data, and get an encrypted result that they can hand back to whoever has the decryption key for the original data, without the third party being able to decrypt the data or the result themselves.

As a simple example, imagine that you have a set of emails, and you want to use a third party spam filter to check whether or not they are spam. The spam filter has a desire for privacy of their algorithm: either the spam filter provider wants to keep their source code closed, or the spam filter depends on a very large database that they do not want to reveal publicly as that would make attacking easier, or both. However, you care about the privacy of your data, and don't want to upload your unencrypted emails to a third party. So here's how you do it:

Fully homomorphic encryption has many applications, including in the blockchain space. One key example is that can be used to implement privacy-preserving light clients (the light client hands the server an encrypted index

i, the server computes and returnsdata[0] * (i = 0) + data[1] * (i = 1) + ... + data[n] * (i = n), wheredata[i]is the i'th piece of data in a block or state along with its Merkle branch and(i = k)is an expression that returns 1 ifi = kand otherwise 0; the light client gets the data it needs and the server learns nothing about what the light client asked).It can also be used for:

And it turns out that fully homomorphic encryption is, conceptually, not that difficult to understand!

Partially, Somewhat, Fully homomorphic encryption

First, a note on definitions. There are different kinds of homomorphic encryption, some more powerful than others, and they are separated by what kinds of functions one can compute on the encrypted data.

encrypt(a)andencrypt(b)you can computeencrypt(a+b)), or just multiplications (givenencrypt(a)andencrypt(b)you can computeencrypt(a*b)).encrypt(x1) ... encrypt(xn)(assuming these are "original" encryptions and not already the result of homomorphic computation), you can computeencrypt(p(x1 ... xn)), as long asp(x1 ... xn)is a polynomial with degree< Dfor some specific degree boundD(Dis usually very low, think 5-15).AND(x, y) = x*y,OR(x, y) = x+y-x*y,XOR(x, y) = x+y-2*x*yor justx+yif you only care about even vs odd,NOT(x) = 1-x...), so this is sufficient to do arbitrary computation on encrypted data.Partially homomorphic encryption is fairly easy; eg. RSA has a multiplicative homomorphism: \(enc(x) = x^e\), \(enc(y) = y^e\), so \(enc(x) * enc(y) = (xy)^e = enc(xy)\). Elliptic curves can offer similar properties with addition. Allowing both addition and multiplication is, it turns out, significantly harder.

A simple somewhat-HE algorithm

Here, we will go through a somewhat-homomorphic encryption algorithm (ie. one that supports a limited number of multiplications) that is surprisingly simple. A more complex version of this category of technique was used by Craig Gentry to create the first-ever fully homomorphic scheme in 2009. More recent efforts have switched to using different schemes based on vectors and matrices, but we will still go through this technique first.

We will describe all of these encryption schemes as secret-key schemes; that is, the same key is used to encrypt and decrypt. Any secret-key HE scheme can be turned into a public key scheme easily: a "public key" is typically just a set of many encryptions of zero, as well as an encryption of one (and possibly more powers of two). To encrypt a value, generate it by adding together the appropriate subset of the non-zero encryptions, and then adding a random subset of the encryptions of zero to "randomize" the ciphertext and make it infeasible to tell what it represents.

The secret key here is a large prime, \(p\) (think of \(p\) as having hundreds or even thousands of digits). The scheme can only encrypt 0 or 1, and "addition" becomes XOR, ie. 1 + 1 = 0. To encrypt a value \(m\) (which is either 0 or 1), generate a large random value \(R\) (this will typically be even larger than \(p\)) and a smaller random value \(r\) (typically much smaller than \(p\)), and output:

\[enc(m) = R * p + r * 2 + m\]

To decrypt a ciphertext \(ct\), compute:

\[dec(ct) = (ct\ mod\ p)\ mod\ 2\]

To add two ciphertexts \(ct_1\) and \(ct_2\), you simply, well, add them: \(ct_1 + ct_2\). And to multiply two ciphertexts, you once again... multiply them: \(ct_1 * ct_2\). We can prove the homomorphic property (that the sum of the encryptions is an encryption of the sum, and likewise for products) as follows.

Let:

\[ct_1 = R_1 * p + r_1 * 2 + m_1\] \[ct_2 = R_2 * p + r_2 * 2 + m_2\]

We add:

\[ct_1 + ct_2 = R_1 * p + R_2 * p + r_1 * 2 + r_2 * 2 + m_1 + m_2\]

Which can be rewritten as:

\[(R_1 + R_2) * p + (r_1 + r_2) * 2 + (m_1 + m_2)\]

Which is of the exact same "form" as a ciphertext of \(m_1 + m_2\). If you decrypt it, the first \(mod\ p\) removes the first term, the second \(mod\ 2\) removes the second term, and what's left is \(m_1 + m_2\) (remember that if \(m_1 = 1\) and \(m_2 = 1\) then the 2 will get absorbed into the second term and you'll be left with zero). And so, voila, we have additive homomorphism!

Now let's check multiplication:

\[ct_1 * ct_2 = (R_1 * p + r_1 * 2 + m_1) * (R_2 * p + r_2 * 2 + m_2)\]

Or:

\[(R_1 * R_2 * p + r_1 * 2 + m_1 + r_2 * 2 + m_2) * p + \] \[(r_1 * r_2 * 2 + r_1 * m_2 + r_2 * m_1) * 2 + \] \[(m_1 * m_2)\]

This was simply a matter of expanding the product above, and grouping together all the terms that contain \(p\), then all the remaining terms that contain \(2\), and finally the remaining term which is the product of the messages. If you decrypt, then once again the \(mod\ p\) removes the first group, the \(mod\ 2\) removes the second group, and only \(m_1 * m_2\) is left.

But there are two problems here: first, the size of the ciphertext itself grows (the length roughly doubles when you multiply), and second, the "noise" (also often called "error") in the smaller \(\* 2\) term also gets quadratically bigger. Adding this error into the ciphertexts was necessary because the security of this scheme is based on the approximate GCD problem:

Had we instead used the "exact GCD problem", breaking the system would be easy: if you just had a set of expressions of the form \(p * R_1 + m_1\), \(p * R_2 + m_2\)..., then you could use the Euclidean algorithm to efficiently compute the greatest common divisor \(p\). But if the ciphertexts are only approximate multiples of \(p\) with some "error", then extracting \(p\) quickly becomes impractical, and so the scheme can be secure.

Unfortunately, the error introduces the inherent limitation that if you multiply the ciphertexts by each other enough times, the error eventually grows big enough that it exceeds \(p\), and at that point the \(mod\ p\) and \(mod\ 2\) steps "interfere" with each other, making the data unextractable. This will be an inherent tradeoff in all of these homomorphic encryption schemes: extracting information from approximate equations "with errors" is much harder than extracting information from exact equations, but any error you add quickly increases as you do computations on encrypted data, bounding the amount of computation that you can do before the error becomes overwhelming. And this is why these schemes are only "somewhat" homomorphic.

Bootstrapping

There are two classes of solution to this problem. First, in many somewhat homomorphic encryption schemes, there are clever tricks to make multiplication only increase the error by a constant factor (eg. 1000x) instead of squaring it. Increasing the error by 1000x still sounds by a lot, but keep in mind that if \(p\) (or its equivalent in other schemes) is a 300-digit number, that means that you can multiply numbers by each other 100 times, which is enough to compute a very wide class of computations. Second, there is Craig Gentry's technique of "bootstrapping".

Suppose that you have a ciphertext \(ct\) that is an encryption of some \(m\) under a key \(p\), that has a lot of error. The idea is that we "refresh" the ciphertext by turning it into a new ciphertext of \(m\) under another key \(p_2\), where this process "clears out" the old error (though it will introduce a fixed amount of new error). The trick is quite clever. The holder of \(p\) and \(p_2\) provides a "bootstrapping key" that consists of an encryption of the bits of \(p\) under the key \(p_2\), as well as the public key for \(p_2\). Whoever is doing computations on data encrypted under \(p\) would then take the bits of the ciphertext \(ct\), and individually encrypt these bits under \(p_2\). They would then homomorphically compute the decryption under \(p\) using these ciphertexts, and get out the single bit, which would be \(m\) encrypted under \(p_2\).

This is difficult to understand, so we can restate it as follows. The decryption procedure \(dec(ct, p)\) is itself a computation, and so it can itself be implemented as a circuit that takes as input the bits of \(ct\) and the bits of \(p\), and outputs the decrypted bit \(m \in {0, 1}\). If someone has a ciphertext \(ct\) encrypted under \(p\), a public key for \(p_2\), and the bits of \(p\) encrypted under \(p_2\), then they can compute \(dec(ct, p) = m\) "homomorphically", and get out \(m\) encrypted under \(p_2\). Notice that the decryption procedure itself washes away the old error; it just outputs 0 or 1. The decryption procedure is itself a circuit, which contains additions or multiplications, so it will introduce new error, but this new error does not depend on the amount of error in the original encryption.

(Note that we can avoid having a distinct new key \(p_2\) (and if you want to bootstrap multiple times, also a \(p_3\), \(p_4\)...) by just setting \(p_2 = p\). However, this introduces a new assumption, usually called "circular security"; it becomes more difficult to formally prove security if you do this, though many cryptographers think it's fine and circular security poses no significant risk in practice)

But.... there is a catch. In the scheme as described above (using circular security or not), the error blows up so quickly that even the decryption circuit of the scheme itself is too much for it. That is, the new \(m\) encrypted under \(p_2\) would already have so much error that it is unreadable. This is because each AND gate doubles the bit-length of the error, so a scheme using a \(d\)-bit modulus \(p\) can only handle less than \(log(d)\) multiplications (in series), but decryption requires computing \(mod\ p\) in a circuit made up of these binary logic gates, which requires... more than \(log(d)\) multiplications.

Craig Gentry came up with clever techniques to get around this problem, but they are arguably too complicated to explain; instead, we will skip straight to newer work from 2011 and 2013, that solves this problem in a different way.

Learning with errors

To move further, we will introduce a different type of somewhat-homomorphic encryption introduced by Brakerski and Vaikuntanathan in 2011, and show how to bootstrap it. Here, we will move away from keys and ciphertexts being integers, and instead have keys and ciphertexts be vectors. Given a key \(k = {k_1, k_2 .... k_n}\), to encrypt a message \(m\), construct a vector \(c = {c_1, c_2 ... c_n}\) such that the inner product (or "dot product") \(<c, k> = c_1k_1 + c_2k_1 + ... + c_nk_n\), modulo some fixed number \(p\), equals \(m+2e\) where \(m\) is the message (which must be 0 or 1), and \(e\) is a small (much smaller than \(p\)) "error" term. A "public key" that allows encryption but not decryption can be constructed, as before, by making a set of encryptions of 0; an encryptor can randomly combine a subset of these equations and add 1 if the message they are encrypting is 1. To decrypt a ciphertext \(c\) knowing the key \(k\), you would compute \(<c, k>\) modulo \(p\), and see if the result is odd or even (this is the same "mod p mod 2" trick we used earlier). Note that here the \(mod\ p\) is typically a "symmetric" mod, that is, it returns a number between \(-\frac{p}{2}\) and \(\frac{p}{2}\) (eg. 137 mod 10 = -3, 212 mod 10 = 2); this allows our error to be positive or negative. Additionally, \(p\) does not necessarily have to be prime, though it does need to be odd.

In this example, we set the modulus \(p = 103\). The dot product is

3 * 2 + 14 * 71 + 15 * 82 + 92 * 81 + 65 * 8 = 10202, and \(10202 = 99 * 103 + 5\). 5 itself is of course \(2 * 2 + 1\), so the message is 1. Note that in practice, the first element of the key is often set to \(1\); this makes it easier to generate ciphertexts for a particular value (see if you can figure out why).The security of the scheme is based on an assumption known as "learning with errors" (LWE) - or, in more jargony but also more understandable terms, the hardness of solving systems of equations with errors.

A ciphertext can itself be viewed as an equation: \(k_1c_1 + .... + k_nc_n \approx 0\), where the key \(k_1 ... k_n\) is the unknowns, the ciphertext \(c_1 ... c_n\) is the coefficients, and the equality is only approximate because of both the message (0 or 1) and the error (\(2e\) for some relatively small \(e\)). The LWE assumption ensures that even if you have access to many of these ciphertexts, you cannot recover \(k\).

Note that in some descriptions of LWE, <c, k> can equal any value, but this value must be provided as part of the ciphertext. This is mathematically equivalent to the <c, k> = m+2e formulation, because you can just add this answer to the end of the ciphertext and add -1 to the end of the key, and get two vectors that when multiplied together just give m+2e. We'll use the formulation that requires <c, k> to be near-zero (ie. just m+2e) because it is simpler to work with.

Multiplying ciphertexts

It is easy to verify that the encryption is additive: if \(<ct_1, k> = 2e_1 + m_1\) and \(<ct_2, k> = 2e_2 + m_2\), then \(<ct_1 + ct_2, k> = 2(e_1 + e_2) + m_1 + m_2\) (the addition here is modulo \(p\)). What is harder is multiplication: unlike with numbers, there is no natural way to multiply two length-n vectors into another length-n vector. The best that we can do is the outer product: a vector containing the products of each possible pair where the first element comes from the first vector and the second element comes from the second vector. That is, \(a \otimes b = a_1b_1 + a_2b_1 + ... + a_nb_1 + a_1b_2 + ... + a_nb_2 + ... + a_nb_n\). We can "multiply ciphertexts" using the convenient mathematical identity \(<a \otimes b, c \otimes d> = <a, c> * <b, d>\).

Given two ciphertexts \(c_1\) and \(c_2\), we compute the outer product \(c_1 \otimes c_2\). If both \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) were encrypted with \(k\), then \(<c_1, k> = 2e_1 + m_1\) and \(<c_2, k> = 2e_2 + m_2\). The outer product \(c_1 \otimes c_2\) can be viewed as an encryption of \(m_1 * m_2\) under \(k \otimes k\); we can see this by looking what happens when we try to decrypt with \(k \otimes k\):

\[<c_1 \otimes c_2, k \otimes k>\] \[= <c_1, k> * <c_2, k>\] \[ = (2e_1 + m_1) * (2e_2 + m_2)\] \[ = 2(e_1m_2 + e_2m_1 + 2e_1e_2) + m_1m_2\]

So this outer-product approach works. But there is, as you may have already noticed, a catch: the size of the ciphertext, and the key, grows quadratically.

Relinearization

We solve this with a relinearization procedure. The holder of the private key \(k\) provides, as part of the public key, a "relinearization key", which you can think of as "noisy" encryptions of \(k \otimes k\) under \(k\). The idea is that we provide these encrypted pieces of \(k \otimes k\) to anyone performing the computations, allowing them to compute the equation \(<c_1 \otimes c_2, k \otimes k>\) to "decrypt" the ciphertext, but only in such a way that the output comes back encrypted under \(k\).

It's important to understand what we mean here by "noisy encryptions". Normally, this encryption scheme only allows encrypting \(m \in \{0,1\}\), and an "encryption of \(m\)" is a vector \(c\) such that \(<c, k> = m+2e\) for some small error \(e\). Here, we're "encrypting" arbitrary \(m \in \{0,1, 2....p-1\}\). Note that the error means that you can't fully recover \(m\) from \(c\); your answer will be off by some multiple of 2. However, it turns out that, for this specific use case, this is fine.

The relinearization key consists of a set of vectors which, when inner-producted (modulo \(p\)) with the key \(k\), give values of the form \(k_i * k_j * 2^d + 2e\) (mod \(p\)), one such vector for every possible triple \((i, j, d)\), where \(i\) and \(j\) are indices in the key and \(d\) is an exponent where \(2^d < p\) (note: if the key has length \(n\), there would be \(n^2 * log(p)\) values in the relinearization key; make sure you understand why before continuing).

Now, let us take a step back and look again at our goal. We have a ciphertext which, if decrypted with \(k \otimes k\), gives \(m_1 * m_2\). We want a ciphertext which, if decrypted with \(k\), gives \(m_1 * m_2\). We can do this with the relinearization key. Notice that the decryption equation \(<ct_1 \otimes ct_2, k \otimes k>\) is just a big sum of terms of the form \((ct_{1_i} * ct_{2_j}) * k_p * k_q\).

And what do we have in our relinearization key? A bunch of elements of the form \(2^d * k_p * k_q\), noisy-encrypted under \(k\), for every possible combination of \(p\) and \(q\)! Having all the powers of two in our relinearization key allows us to generate any \((ct_{1_i} * ct_{2_j}) * k_p * k_q\) by just adding up \(\le log(p)\) powers of two (eg. 13 = 8 + 4 + 1) together for each \((p, q)\) pair.

For example, if \(ct_1 = [1, 2]\) and \(ct_2 = [3, 4]\), then \(ct_1 \otimes ct_2 = [3, 4, 6, 8]\), and \(enc(<ct_1 \otimes ct_2, k \otimes k>) = enc(3k_1k_1 + 4k_1k_2 + 6k_2k_1 + 8k_2k_2)\) could be computed via:

\[enc(k_1 * k_1) + enc(k_1 * k_1 * 2) + enc(k_1 * k_2 * 4) + \]

\[enc(k_2 * k_1 * 2) + enc(k_2 * k_1 * 4) + enc(k_2 * k_2 * 8) \]

Note that each noisy-encryption in the relinearization key has some even error \(2e\), and the equation \(<ct_1 \otimes ct_2, k \otimes k>\) itself has some error: if \(<ct_1, k> = 2e_1 + m_1\) and \(<ct_2 + k> = 2e_2 + m_2\), then \(<ct_1 \otimes ct_2, k \otimes k> =\) \(<ct_1, k> * <ct_2 + k> =\) \(2(2e_1e_2 + e_1m_2 + e_2m_1) + m_1m_2\). But this total error is still (relatively) small (\(2e_1e_2 + e_1m_2 + e_2m_1\) plus \(n^2 * log(p)\) fixed-size errors from the realinearization key), and the error is even, and so the result of this calculation still gives a value which, when inner-producted with \(k\), gives \(m_1 * m_2 + 2e'\) for some "combined error" \(e'\).

The broader technique we used here is a common trick in homomorphic encryption: provide pieces of the key encrypted under the key itself (or a different key if you are pedantic about avoiding circular security assumptions), such that someone computing on the data can compute the decryption equation, but only in such a way that the output itself is still encrypted. It was used in bootstrapping above, and it's used here; it's best to make sure you mentally understand what's going on in both cases.

This new ciphertext has considerably more error in it: the \(n^2 * log(p)\) different errors from the portions of the relinearization key that we used, plus the \(2(2e_1e_2 + e_1m_2 + e_2m_1)\) from the original outer-product ciphertext. Hence, the new ciphertext still does have quadratically larger error than the original ciphertexts, and so we still haven't solved the problem that the error blows up too quickly. To solve this, we move on to another trick...

Modulus switching

Here, we need to understand an important algebraic fact. A ciphertext is a vector \(ct\), such that \(<ct, k> = m+2e\), where \(m \in \{0,1\}\). But we can also look at the ciphertext from a different "perspective": consider \(\frac{ct}{2}\) (modulo \(p\)). \(<\frac{ct}{2}, k> = \frac{m}{2} + e\), where \(\frac{m}{2} \in \{0,\frac{p+1}{2}\}\). Note that because (modulo \(p\)) \((\frac{p+1}{2})*2 = p+1 = 1\), division by 2 (modulo \(p\)) maps \(1\) to \(\frac{p+1}{2}\); this is a very convenient fact for us.

The scheme in this section uses both modular division (ie. multiplying by the modular multiplicative inverse) and regular "rounded down" integer division; make sure you understand how both work and how they are different from each other.

That is, the operation of dividing by 2 (modulo \(p\)) converts small even numbers into small numbers, and it converts 1 into \(\frac{p}{2}\) (rounded up). So if we look at \(\frac{ct}{2}\) (modulo \(p\)) instead of \(ct\), decryption involves computing \(<\frac{ct}{2}, k>\) and seeing if it's closer to \(0\) or \(\frac{p}{2}\). This "perspective" is much more robust to certain kinds of errors, where you know the error is small but can't guarantee that it's a multiple of 2.

Now, here is something we can do to a ciphertext.

Step 3 is the crucial one: it converts a ciphertext under modulus \(p\) into a ciphertext under modulus \(q\). The process just involves "scaling down" each element of \(ct'\) by multiplying by \(\frac{q}{p}\) and rounding down, eg. \(floor(56 * \frac{15}{103}) = floor(8.15533..) = 8\).

The idea is this: if \(<ct', k> = m*\frac{p}{2} + e\ (mod\ p)\), then we can interpret this as \(<ct', k> = p(z + \frac{m}{2}) + e\) for some integer \(z\). Therefore, \(<ct' * \frac{q}{p}, k> = q(z + \frac{m}{2}) + e*\frac{p}{q}\). Rounding adds error, but only a little bit (specifically, up to the size of the values in \(k\), and we can make the values in \(k\) small without sacrificing security). Therefore, we can say \(<ct' * \frac{q}{p}, k> = m*\frac{q}{2} + e' + e_2\ (mod\ q)\), where \(e' = e * \frac{q}{p}\), and \(e_2\) is a small error from rounding.

What have we accomplished? We turned a ciphertext with modulus \(p\) and error \(2e\) into a ciphertext with modulus \(q\) and error \(2(floor(e*\frac{p}{q}) + e_2)\), where the new error is smaller than the original error.

Let's go through the above with an example. Suppose:

\(<ct, k> = 5612 * 9 = 50508 = 9999 * 5 + 2 * 256 + 1\), so \(ct\) represents the bit 1, but the error is fairly large (\(e = 256\)).

Step 2: \(ct' = \frac{ct}{2} = 2806\) (remember this is modular division; if \(ct\) were instead \(5613\), then we would have \(\frac{ct}{2} = 7806\)). Checking: \(<ct', k> = 2806 * 9 = 25254 = 9999 * 2.5 + 256.5\)

Step 3: \(ct'' = floor(2806 * \frac{113}{9999}) = floor(31.7109...) = 31\). Checking: \(<ct'', k> = 279 = 113 * 2.5 - 3.5\)

Step 4: \(ct''' = 31 * 2 = 62\). Checking: \(<ct''', k> = 558 = 113 * 5 - 2 * 4 + 1\)

And so the bit \(1\) is preserved through the transformation. The crazy thing about this procedure is: none of it requires knowing \(k\). Now, an astute reader might notice: you reduced the absolute size of the error (from 256 to 2), but the relative size of the error remained unchanged, and even slightly increased: \(\frac{256}{9999} \approx 2.5\%\) but \(\frac{4}{113} \approx 3.5\%\). Given that it's the relative error that causes ciphertexts to break, what have we gained here?

The answer comes from what happens to error when you multiply ciphertexts. Suppose that we start with a ciphertext \(x\) with error 100, and modulus \(p = 10^{16} - 1\). We want to repeatedly square \(x\), to compute \((((x^2)^2)^2)^2 = x^{16}\). First, the "normal way":

The error blows up too quickly for the computation to be possible. Now, let's do a modulus reduction after every multiplication. We assume the modulus reduction is imperfect and increases error by a factor of 10, so a 1000x modulo reduction only reduces error from 10000 to 100 (and not to 10):

The key mathematical idea here is that the factor by which error increases in a multiplication depends on the absolute size of the error, and not its relative size, and so if we keep doing modulus reductions to keep the error small, each multiplication only increases the error by a constant factor. And so, with a \(d\) bit modulus (and hence \(\approx 2^d\) room for "error"), we can do \(O(d)\) multiplications! This is enough to bootstrap.

Another technique: matrices

Another technique (see Gentry, Sahai, Waters (2013)) for fully homomorphic encryption involves matrices: instead of representing a ciphertext as \(ct\) where \(<ct, k> = 2e + m\), a ciphertext is a matrix, where \(k * CT = k * m + e\) (\(k\), the key, is still a vector). The idea here is that \(k\) is a "secret near-eigenvector" - a secret vector which, if you multiply the matrix by it, returns something very close to either zero or the key itself.

The fact that addition works is easy: if \(k * CT_1 = m_1 * k + e_1\) and \(k * CT_2 = m_2 * k + e_2\), then \(k * (CT_1 + CT_2) = (m_1 + m_2) * k + (e_1 + e_2)\). The fact that multiplication works is also easy:

\(k * CT_1 * CT_2\) \(= (m_1 * k + e_1) * CT_2\) \(= m_1 * k * CT_2 + e_1 * CT_2\) \(= m_1 * m_2 * k + m_1 * e_2 + e_1 * CT_2\)

The first term is the "intended term"; the latter two terms are the "error". That said, notice that here error does blow up quadratically (see the \(e_1 * CT_2\) term; the size of the error increases by the size of each ciphertext element, and the ciphertext elements also square in size), and you do need some clever tricks for avoiding this. Basically, this involves turning ciphertexts into matrices containing their constituent bits before multiplying, to avoid multiplying by anything higher than 1; if you want to see how this works in detail I recommend looking at my code: https://github.com/vbuterin/research/blob/master/matrix_fhe/matrix_fhe.py#L121

In addition, the code there, and also https://github.com/vbuterin/research/blob/master/tensor_fhe/homomorphic_encryption.py#L186, provides simple examples of useful circuits that you can build out of these binary logical operations; the main example is for adding numbers that are represented as multiple bits, but one can also make circuits for comparison (\(<\), \(>\), \(=\)), multiplication, division, and many other operations.

Since 2012-13, when these algorithms were created, there have been many optimizations, but they all work on top of these basic frameworks. Often, polynomials are used instead of integers; this is called ring LWE. The major challenge is still efficiency: an operation involving a single bit involves multiplying entire matrices or performing an entire relinearization computation, a very high overhead. There are tricks that allow you to perform many bit operations in a single ciphertext operation, and this is actively being worked on and improved.

We are quickly getting to the point where many of the applications of homomorphic encryption in privacy-preserving computation are starting to become practical. Additionally, research in the more advanced applications of the lattice-based cryptography used in homomorphic encryption is rapidly progressing. So this is a space where some things can already be done today, but we can hopefully look forward to much more becoming possible over the next decade.