A Guide to 99% Fault Tolerant Consensus

2018 Aug 07

See all posts

A Guide to 99% Fault Tolerant Consensus

Special thanks to Emin Gun Sirer for review

We've heard for a long time that it's possible to achieve consensus

with 50% fault tolerance in a synchronous network where messages

broadcasted by any honest node are guaranteed to be received by all

other honest nodes within some known time period (if an attacker has

more than 50%, they can perform a "51% attack", and there's an

analogue of this for any algorithm of this type). We've also heard for a

long time that if you want to relax the synchrony assumption, and have

an algorithm that's "safe under asynchrony", the maximum achievable

fault tolerance drops to 33% (PBFT, Casper FFG, etc all fall

into this category). But did you know that if you add even more

assumptions (specifically, you require observers, ie. users

that are not actively participating in the consensus but care about its

output, to also be actively watching the consensus, and not just

downloading its output after the fact), you can increase fault tolerance

all the way to 99%?

This has in fact been known for a long time; Leslie Lamport's famous

1982 paper "The Byzantine Generals Problem" (link here)

contains a description of the algorithm. The following will be my

attempt to describe and reformulate the algorithm in a simplified

form.

Suppose that there are \(N\)

consensus-participating nodes, and everyone agrees who these nodes are

ahead of time (depending on context, they could have been selected by a

trusted party or, if stronger decentralization is desired, by some proof

of work or proof of stake scheme). We label these nodes \(0 ...N-1\). Suppose also that there is a

known bound \(D\) on network latency

plus clock disparity (eg. \(D\) = 8

seconds). Each node has the ability to publish a value at time \(T\) (a malicious node can of course propose

values earlier or later than \(T\)).

All nodes wait \((N-1) \cdot D\)

seconds, running the following process. Define \(x : i\) as "the value \(x\) signed by node \(i\)", \(x : i :

j\) as "the value \(x\) signed

by \(i\), and that value and signature

together signed by \(j\)", etc. The

proposals published in the first stage will be of the form \(v: i\) for some \(v\) and \(i\), containing the signature of the node

that proposed it.

If a validator \(i\) receives some

message \(v : i[1] : ... : i[k]\),

where \(i[1] ... i[k]\) is a list of

indices that have (sequentially) signed the message already (just \(v\) by itself would count as \(k=0\), and \(v:i\) as \(k=1\)), then the validator checks that (i)

the time is less than \(T + k \cdot

D\), and (ii) they have not yet seen a valid message containing

\(v\); if both checks pass, they

publish \(v : i[1] : ... : i[k] :

i\).

At time \(T + (N-1) \cdot D\), nodes

stop listening. At this point, there is a guarantee that honest nodes

have all "validly seen" the same set of values.

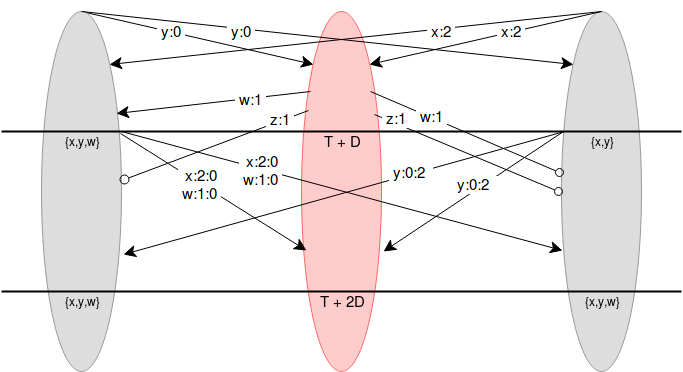

Node 1 (red) is malicious, and nodes 0 and 2 (grey) are

honest. At the start, the two honest nodes make their proposals \(y\) and \(x\), and the attacker proposes both \(w\) and \(z\) late. \(w\) reaches node 0 on time but not node 2,

and \(z\) reaches neither node on time.

At time \(T + D\), nodes 0 and 2

rebroadcast all values they've seen that they have not yet broadcasted,

but add their signatures on (\(x\) and

\(w\) for node 0, \(y\) for node 2). Both honest nodes saw

\({x, y, w}\).

If the problem demands choosing one value, they can use some "choice"

function to pick a single value out of the values they have seen (eg.

they take the one with the lowest hash). The nodes can then agree on

this value.

Now, let's explore why this works. What we need to prove is that if

one honest node has seen a particular value (validly), then every other

honest node has also seen that value (and if we prove this, then we know

that all honest nodes have seen the same set of values, and so if all

honest nodes are running the same choice function, they will choose the

same value). Suppose that any honest node receives a message \(v : i[1] : ... : i[k]\) that they perceive

to be valid (ie. it arrives before time \(T +

k \cdot D\)). Suppose \(x\) is

the index of a single other honest node. Either \(x\) is part of \({i[1] ... i[k]}\) or it is not.

- In the first case (say \(x = i[j]\)

for this message), we know that the honest node \(x\) had already broadcasted that message,

and they did so in response to a message with \(j-1\) signatures that they received before

time \(T + (j-1) \cdot D\), so they

broadcast their message at that time, and so the message must have been

received by all honest nodes before time \(T +

j \cdot D\).

- In the second case, since the honest node sees the message before

time \(T + k \cdot D\), then they will

broadcast the message with their signature and guarantee that everyone,

including \(x\), will see it before

time \(T + (k+1) \cdot D\).

Notice that the algorithm uses the act of adding one's own signature

as a kind of "bump" on the timeout of a message, and it's this ability

that guarantees that if one honest node saw a message on time, they can

ensure that everyone else sees the message on time as well, as the

definition of "on time" increments by more than network latency with

every added signature.

In the case where one node is honest, can we guarantee that passive

observers (ie. non-consensus-participating nodes that care

about knowing the outcome) can also see the outcome, even if we require

them to be watching the process the whole time? With the scheme as

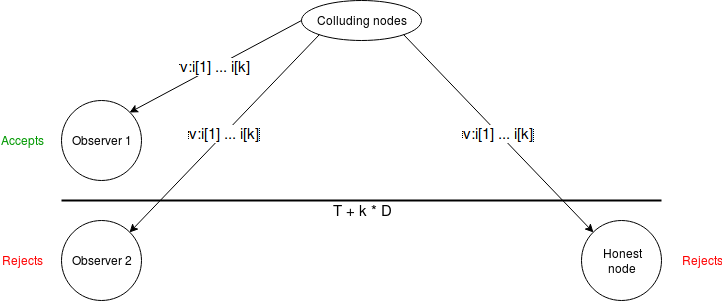

written, there's a problem. Suppose that a commander and some subset of

\(k\) (malicious) validators produce a

message \(v : i[1] : .... : i[k]\), and

broadcast it directly to some "victims" just before time \(T + k \cdot D\). The victims see the

message as being "on time", but when they rebroadcast it, it only

reaches all honest consensus-participating nodes after \(T + k \cdot D\), and so all honest

consensus-participating nodes reject it.

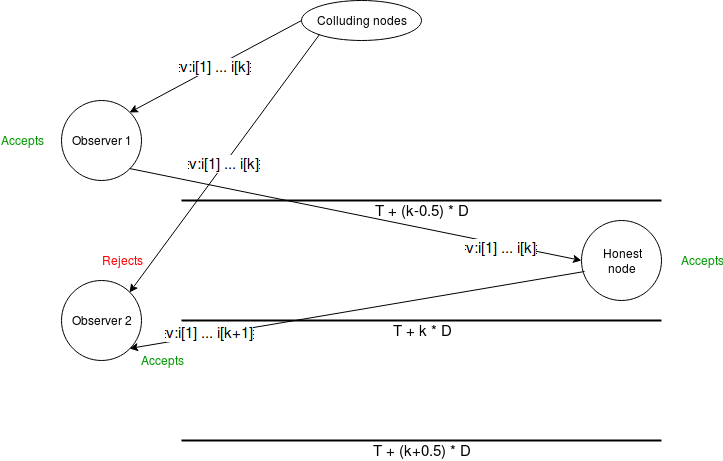

But we can plug this hole. We require \(D\) to be a bound on two times

network latency plus clock disparity. We then put a different timeout on

observers: an observer accepts \(v : i[1] :

.... : i[k]\) before time \(T + (k -

0.5) \cdot D\). Now, suppose an observer sees a message an

accepts it. They will be able to broadcast it to an honest node before

time \(T + k \cdot D\), and the honest

node will issue the message with their signature attached, which will

reach all other observers before time \(T + (k

+ 0.5) \cdot D\), the timeout for messages with \(k+1\) signatures.

Retrofitting onto

other consensus algorithms

The above could theoretically be used as a standalone consensus

algorithm, and could even be used to run a proof-of-stake blockchain.

The validator set of round \(N+1\) of

the consensus could itself be decided during round \(N\) of the consensus (eg. each round of a

consensus could also accept "deposit" and "withdraw" transactions, which

if accepted and correctly signed would add or remove validators into the

next round). The main additional ingredient that would need to be added

is a mechanism for deciding who is allowed to propose blocks (eg. each

round could have one designated proposer). It could also be modified to

be usable as a proof-of-work blockchain, by allowing

consensus-participating nodes to "declare themselves" in real time by

publishing a proof of work solution on top of their public key at th

same time as signing a message with it.

However, the synchrony assumption is very strong, and so we would

like to be able to work without it in the case where we don't need more

than 33% or 50% fault tolerance. There is a way to accomplish this.

Suppose that we have some other consensus algorithm (eg. PBFT, Casper

FFG, chain-based PoS) whose output can be seen by

occasionally-online observers (we'll call this the

threshold-dependent consensus algorithm, as opposed to the

algorithm above, which we'll call the latency-dependent

consensus algorithm). Suppose that the threshold-dependent consensus

algorithm runs continuously, in a mode where it is constantly

"finalizing" new blocks onto a chain (ie. each finalized value points to

some previous finalized value as a "parent"; if there's a sequence of

pointers \(A \rightarrow ... \rightarrow

B\), we'll call \(A\) a

descendant of \(B\)).

We can retrofit the latency-dependent algorithm onto this structure,

giving always-online observers access to a kind of "strong finality" on

checkpoints, with fault tolerance ~95% (you can push this arbitrarily

close to 100% by adding more validators and requiring the process to

take longer).

Every time the time reaches some multiple of 4096 seconds, we run the

latency-dependent algorithm, choosing 512 random nodes to participate in

the algorithm. A valid proposal is any valid chain of values that were

finalized by the threshold-dependent algorithm. If a node sees some

finalized value before time \(T + k \cdot

D\) (\(D\) = 8 seconds) with

\(k\) signatures, it accepts the chain

into its set of known chains and rebroadcasts it with its own signature

added; observers use a threshold of \(T + (k -

0.5) \cdot D\) as before.

The "choice" function used at the end is simple:

- Finalized values that are not descendants of what was already agreed

to be a finalized value in the previous round are ignored

- Finalized values that are invalid are ignored

- To choose between two valid finalized values, pick the one with the

lower hash

If 5% of validators are honest, there is only a roughly 1 in 1

trillion chance that none of the 512 randomly selected nodes will be

honest, and so as long as the network latency plus clock disparity is

less than \(\frac{D}{2}\) the above

algorithm will work, correctly coordinating nodes on some single

finalized value, even if multiple conflicting finalized values are

presented because the fault tolerance of the threshold-dependent

algorithm is broken.

If the fault tolerance of the threshold-dependent consensus algorithm

is met (usually 50% or 67% honest), then the threshold-dependent

consensus algorithm will either not finalize any new checkpoints, or it

will finalize new checkpoints that are compatible with each other (eg. a

series of checkpoints where each points to the previous as a parent), so

even if network latency exceeds \(\frac{D}{2}\) (or even \(D\)), and as a result nodes participating

in the latency-dependent algorithm disagree on which value they accept,

the values they accept are still guaranteed to be part of the same chain

and so there is no actual disagreement. Once latency recovers back to

normal in some future round, the latency-dependent consensus will get

back "in sync".

If the assumptions of both the threshold-dependent and

latency-dependent consensus algorithms are broken at the same

time (or in consecutive rounds), then the algorithm can break down.

For example, suppose in one round, the threshold-dependent consensus

finalizes \(Z \rightarrow Y \rightarrow

X\) and the latency-dependent consensus disagrees between \(Y\) and \(X\), and in the next round the

threshold-dependent consensus finalizes a descendant \(W\) of \(X\) which is not a descendant of

\(Y\); in the latency-dependent

consensus, the nodes who agreed \(Y\)

will not accept \(W\), but the nodes

that agreed \(X\) will. However, this

is unavoidable; the impossibility of safe-under-asynchrony consensus

with more than \(\frac{1}{3}\) fault

tolerance is a well

known result in Byzantine fault tolerance theory, as is the

impossibility of more than \(\frac{1}{2}\) fault tolerance even allowing

synchrony assumptions but assuming offline observers.

A Guide to 99% Fault Tolerant Consensus

2018 Aug 07 See all postsSpecial thanks to Emin Gun Sirer for review

We've heard for a long time that it's possible to achieve consensus with 50% fault tolerance in a synchronous network where messages broadcasted by any honest node are guaranteed to be received by all other honest nodes within some known time period (if an attacker has more than 50%, they can perform a "51% attack", and there's an analogue of this for any algorithm of this type). We've also heard for a long time that if you want to relax the synchrony assumption, and have an algorithm that's "safe under asynchrony", the maximum achievable fault tolerance drops to 33% (PBFT, Casper FFG, etc all fall into this category). But did you know that if you add even more assumptions (specifically, you require observers, ie. users that are not actively participating in the consensus but care about its output, to also be actively watching the consensus, and not just downloading its output after the fact), you can increase fault tolerance all the way to 99%?

This has in fact been known for a long time; Leslie Lamport's famous 1982 paper "The Byzantine Generals Problem" (link here) contains a description of the algorithm. The following will be my attempt to describe and reformulate the algorithm in a simplified form.

Suppose that there are \(N\) consensus-participating nodes, and everyone agrees who these nodes are ahead of time (depending on context, they could have been selected by a trusted party or, if stronger decentralization is desired, by some proof of work or proof of stake scheme). We label these nodes \(0 ...N-1\). Suppose also that there is a known bound \(D\) on network latency plus clock disparity (eg. \(D\) = 8 seconds). Each node has the ability to publish a value at time \(T\) (a malicious node can of course propose values earlier or later than \(T\)). All nodes wait \((N-1) \cdot D\) seconds, running the following process. Define \(x : i\) as "the value \(x\) signed by node \(i\)", \(x : i : j\) as "the value \(x\) signed by \(i\), and that value and signature together signed by \(j\)", etc. The proposals published in the first stage will be of the form \(v: i\) for some \(v\) and \(i\), containing the signature of the node that proposed it.

If a validator \(i\) receives some message \(v : i[1] : ... : i[k]\), where \(i[1] ... i[k]\) is a list of indices that have (sequentially) signed the message already (just \(v\) by itself would count as \(k=0\), and \(v:i\) as \(k=1\)), then the validator checks that (i) the time is less than \(T + k \cdot D\), and (ii) they have not yet seen a valid message containing \(v\); if both checks pass, they publish \(v : i[1] : ... : i[k] : i\).

At time \(T + (N-1) \cdot D\), nodes stop listening. At this point, there is a guarantee that honest nodes have all "validly seen" the same set of values.

Node 1 (red) is malicious, and nodes 0 and 2 (grey) are honest. At the start, the two honest nodes make their proposals \(y\) and \(x\), and the attacker proposes both \(w\) and \(z\) late. \(w\) reaches node 0 on time but not node 2, and \(z\) reaches neither node on time. At time \(T + D\), nodes 0 and 2 rebroadcast all values they've seen that they have not yet broadcasted, but add their signatures on (\(x\) and \(w\) for node 0, \(y\) for node 2). Both honest nodes saw \({x, y, w}\).

If the problem demands choosing one value, they can use some "choice" function to pick a single value out of the values they have seen (eg. they take the one with the lowest hash). The nodes can then agree on this value.

Now, let's explore why this works. What we need to prove is that if one honest node has seen a particular value (validly), then every other honest node has also seen that value (and if we prove this, then we know that all honest nodes have seen the same set of values, and so if all honest nodes are running the same choice function, they will choose the same value). Suppose that any honest node receives a message \(v : i[1] : ... : i[k]\) that they perceive to be valid (ie. it arrives before time \(T + k \cdot D\)). Suppose \(x\) is the index of a single other honest node. Either \(x\) is part of \({i[1] ... i[k]}\) or it is not.

Notice that the algorithm uses the act of adding one's own signature as a kind of "bump" on the timeout of a message, and it's this ability that guarantees that if one honest node saw a message on time, they can ensure that everyone else sees the message on time as well, as the definition of "on time" increments by more than network latency with every added signature.

In the case where one node is honest, can we guarantee that passive observers (ie. non-consensus-participating nodes that care about knowing the outcome) can also see the outcome, even if we require them to be watching the process the whole time? With the scheme as written, there's a problem. Suppose that a commander and some subset of \(k\) (malicious) validators produce a message \(v : i[1] : .... : i[k]\), and broadcast it directly to some "victims" just before time \(T + k \cdot D\). The victims see the message as being "on time", but when they rebroadcast it, it only reaches all honest consensus-participating nodes after \(T + k \cdot D\), and so all honest consensus-participating nodes reject it.

But we can plug this hole. We require \(D\) to be a bound on two times network latency plus clock disparity. We then put a different timeout on observers: an observer accepts \(v : i[1] : .... : i[k]\) before time \(T + (k - 0.5) \cdot D\). Now, suppose an observer sees a message an accepts it. They will be able to broadcast it to an honest node before time \(T + k \cdot D\), and the honest node will issue the message with their signature attached, which will reach all other observers before time \(T + (k + 0.5) \cdot D\), the timeout for messages with \(k+1\) signatures.

Retrofitting onto other consensus algorithms

The above could theoretically be used as a standalone consensus algorithm, and could even be used to run a proof-of-stake blockchain. The validator set of round \(N+1\) of the consensus could itself be decided during round \(N\) of the consensus (eg. each round of a consensus could also accept "deposit" and "withdraw" transactions, which if accepted and correctly signed would add or remove validators into the next round). The main additional ingredient that would need to be added is a mechanism for deciding who is allowed to propose blocks (eg. each round could have one designated proposer). It could also be modified to be usable as a proof-of-work blockchain, by allowing consensus-participating nodes to "declare themselves" in real time by publishing a proof of work solution on top of their public key at th same time as signing a message with it.

However, the synchrony assumption is very strong, and so we would like to be able to work without it in the case where we don't need more than 33% or 50% fault tolerance. There is a way to accomplish this. Suppose that we have some other consensus algorithm (eg. PBFT, Casper FFG, chain-based PoS) whose output can be seen by occasionally-online observers (we'll call this the threshold-dependent consensus algorithm, as opposed to the algorithm above, which we'll call the latency-dependent consensus algorithm). Suppose that the threshold-dependent consensus algorithm runs continuously, in a mode where it is constantly "finalizing" new blocks onto a chain (ie. each finalized value points to some previous finalized value as a "parent"; if there's a sequence of pointers \(A \rightarrow ... \rightarrow B\), we'll call \(A\) a descendant of \(B\)).

We can retrofit the latency-dependent algorithm onto this structure, giving always-online observers access to a kind of "strong finality" on checkpoints, with fault tolerance ~95% (you can push this arbitrarily close to 100% by adding more validators and requiring the process to take longer).

Every time the time reaches some multiple of 4096 seconds, we run the latency-dependent algorithm, choosing 512 random nodes to participate in the algorithm. A valid proposal is any valid chain of values that were finalized by the threshold-dependent algorithm. If a node sees some finalized value before time \(T + k \cdot D\) (\(D\) = 8 seconds) with \(k\) signatures, it accepts the chain into its set of known chains and rebroadcasts it with its own signature added; observers use a threshold of \(T + (k - 0.5) \cdot D\) as before.

The "choice" function used at the end is simple:

If 5% of validators are honest, there is only a roughly 1 in 1 trillion chance that none of the 512 randomly selected nodes will be honest, and so as long as the network latency plus clock disparity is less than \(\frac{D}{2}\) the above algorithm will work, correctly coordinating nodes on some single finalized value, even if multiple conflicting finalized values are presented because the fault tolerance of the threshold-dependent algorithm is broken.

If the fault tolerance of the threshold-dependent consensus algorithm is met (usually 50% or 67% honest), then the threshold-dependent consensus algorithm will either not finalize any new checkpoints, or it will finalize new checkpoints that are compatible with each other (eg. a series of checkpoints where each points to the previous as a parent), so even if network latency exceeds \(\frac{D}{2}\) (or even \(D\)), and as a result nodes participating in the latency-dependent algorithm disagree on which value they accept, the values they accept are still guaranteed to be part of the same chain and so there is no actual disagreement. Once latency recovers back to normal in some future round, the latency-dependent consensus will get back "in sync".

If the assumptions of both the threshold-dependent and latency-dependent consensus algorithms are broken at the same time (or in consecutive rounds), then the algorithm can break down. For example, suppose in one round, the threshold-dependent consensus finalizes \(Z \rightarrow Y \rightarrow X\) and the latency-dependent consensus disagrees between \(Y\) and \(X\), and in the next round the threshold-dependent consensus finalizes a descendant \(W\) of \(X\) which is not a descendant of \(Y\); in the latency-dependent consensus, the nodes who agreed \(Y\) will not accept \(W\), but the nodes that agreed \(X\) will. However, this is unavoidable; the impossibility of safe-under-asynchrony consensus with more than \(\frac{1}{3}\) fault tolerance is a well known result in Byzantine fault tolerance theory, as is the impossibility of more than \(\frac{1}{2}\) fault tolerance even allowing synchrony assumptions but assuming offline observers.