The Triangle of Harm

2017 Jul 16

See all posts

The Triangle of Harm

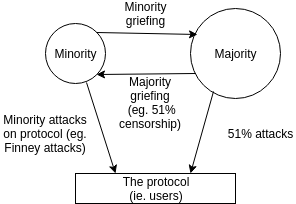

The following is a diagram from a slide that I made in one of my

presentations at Cornell this week:

If there was one diagram that could capture the core

principle of Casper's incentivization philosophy, this might be it.

Hence, it warrants some further explanation.

The diagram shows three constituencies - the minority, the majority

and the protocol (ie. users), and four arrows representing possible

adversarial actions: the minority attacking the protocol, the minority

attacking the majority, the majority attacking the protocol, and the

majority attacking the minority. Examples of each include:

- Minority attacking the protocol - Finney

attacks (an attack done by a miner on a proof of work blockchain

where the miner double-spends unconfirmed, or possibly single-confirmed,

transactions)

- Minority attacking the majority - feather

forking (a minority in a proof of work chain attempting to revert

any block that contains some undesired transactions, though giving up if

the block gets two confirmations)

- Majority attacking the protocol - traditional 51%

attacks

- Majority attacking the minority - a 51% censorship

attack, where a cartel refuses to accept any blocks from miners (or

validators) outside the cartel

The essence of Casper's philosophy is this: for all four

categories of attack, we want to put an upper bound on the

ratio between the amount of harm suffered by the victims of the attack

and the cost to the attacker. In some ways, every design decision in

Casper flows out of this principle.

This differs greatly from the usual proof of work incentivization

school of thought in that in the proof of work view, the last two

attacks are left undefended against. The first two attacks, Finney

attacks and feather forking, are costly because the attacker risks their

blocks not getting included into the chain and so loses revenue. If the

attacker is a majority, however, the attack is costless, because the

attacker can always guarantee that their chain will be the main chain.

In the long run, difficulty adjustment ensures that the total revenue of

all miners is exactly the same no matter what, and this further means

that if an attack causes some victims to lose money, then the attacker

gains money.

This property of proof of work arises because traditional Nakamoto

proof of work fundamentally punishes dissent - if you as a

miner make a block that aligns with the consensus, you get rewarded, and

if you make a block that does not align with the consensus you get

penalized (the penalty is not in the protocol; rather, it comes from the

fact that such a miner expends electricity and capital to produce the

block and gets no reward).

Casper, on the other hand, works primarily by

punishing

equivocation - if you send two messages that conflict with each

other, then you get very heavily penalized, even if one of those

messages aligns with the consensus (read more on this in the

blog

post on "minimal slashing conditions"). Hence, in the event of a

finality reversion attack, those who caused the reversion event are

penalized, and everyone else is left untouched; the majority can attack

the protocol only at heavy cost, and the majority cannot cause the

minority to lose money.

It gets more challenging when we move to talking about two other

kinds of attacks - liveness faults, and censorship. A liveness fault is

one where a large portion of Casper validators go offline, preventing

the consensus from reaching finality, and a censorship fault is one

where a majority of Casper validators refuse to accept some

transactions, or refuse to accept consensus messages from other Casper

validators (the victims) in order to deprive them of rewards.

This touches on a fundamental dichotomy: speaker/listener

fault equivalence.

Suppose that person B says that they did not receive a message from

person A. There are two possible explanations: (i) person A did not send

the message, (ii) person B pretended not to hear the message. Given just

the evidence of B's claim, there is no way to tell which of the two

explanations is correct. The relation to blockchain protocol

incentivization is this: if you see a protocol execution where 70% of

validators' messages are included in the chain and 30% are not, and see

nothing else (and this is what the blockchain sees), then there is no

way to tell whether the problem is that 30% are offline or 70% are

censoring. If we want to make both kinds of attacks expensive, there is

only one thing that we can do: penalize both sides.

Penalizing both sides allows either side to "grief" the other, by

going offline if they are a minority and censoring if they are a

majority. However, we can establish bounds on how easy this griefing is,

through the technique of griefing factor analysis. The

griefing factor of a strategy is essentially the amount of money lost by

the victims divided by the amount of money lost by the attackers, and

the griefing factor of a protocol is the highest griefing factor that it

allows. For example, if a protocol allows me to cause you to lose $3 at

a cost of $1 to myself, then the griefing factor is 3. If there are no

ways to cause others to lose money, the griefing factor is zero, and if

you can cause others to lose money at no cost to yourself (or at a

benefit to yourself), the griefing factor is infinity.

In general, wherever a speaker/listener dichotomy exists, the

griefing factor cannot be globally bounded above by any value below

1. The reason is simple: either side can grief the other, so if

side \(A\) can grief side \(B\) with a factor of \(x\) then side \(B\) can grief side \(A\) with a factor of \(\frac{1}{x}\); \(x\) and \(\frac{1}{x}\) cannot both be below 1

simultaneously. We can play around with the factors; for example, it may

be considered okay to allow griefing factors of 2 for majority attackers

in exchange for keeping the griefing factor at 0.5 for minorities, with

the reasoning that minority attackers are more likely. We can also allow

griefing factors of 1 for small-scale attacks, but specifically for

large-scale attacks force a chain split where on one chain one side is

penalized and on another chain another side is penalized, trusting the

market to pick the chain where attackers are not favored. Hence there is

a lot of room for compromise and making tradeoffs between different

concerns within this framework.

Penalizing both sides has another benefit: it ensures that if the

protocol is harmed, the attacker is penalized. This ensures that whoever

the attacker is, they have an incentive to avoid attacking that is

commensurate with the amount of harm done to the protocol. However, if

we want to bound the ratio of harm to the protocol over cost to

attackers, we need a formalized way of measuring how much harm to the

protocol was done.

This introduces the concept of the protocol utility

function - a formula that tells us how well the protocol is

doing, that should ideally be calculable from inside the blockchain. In

the case of a proof of work chain, this could be the percentage of all

blocks produced that are in the main chain. In Casper, protocol utility

is zero for a perfect execution where every epoch is finalized and no

safety failures ever take place, with some penalty for every epoch that

is not finalized, and a very large penalty for every safety failure. If

a protocol utility function can be formalized, then penalties for faults

can be set as close to the loss of protocol utility resulting from those

faults as possible.

The Triangle of Harm

2017 Jul 16 See all postsIf there was one diagram that could capture the core principle of Casper's incentivization philosophy, this might be it. Hence, it warrants some further explanation.

The diagram shows three constituencies - the minority, the majority and the protocol (ie. users), and four arrows representing possible adversarial actions: the minority attacking the protocol, the minority attacking the majority, the majority attacking the protocol, and the majority attacking the minority. Examples of each include:

The essence of Casper's philosophy is this: for all four categories of attack, we want to put an upper bound on the ratio between the amount of harm suffered by the victims of the attack and the cost to the attacker. In some ways, every design decision in Casper flows out of this principle.

This differs greatly from the usual proof of work incentivization school of thought in that in the proof of work view, the last two attacks are left undefended against. The first two attacks, Finney attacks and feather forking, are costly because the attacker risks their blocks not getting included into the chain and so loses revenue. If the attacker is a majority, however, the attack is costless, because the attacker can always guarantee that their chain will be the main chain. In the long run, difficulty adjustment ensures that the total revenue of all miners is exactly the same no matter what, and this further means that if an attack causes some victims to lose money, then the attacker gains money.

This property of proof of work arises because traditional Nakamoto proof of work fundamentally punishes dissent - if you as a miner make a block that aligns with the consensus, you get rewarded, and if you make a block that does not align with the consensus you get penalized (the penalty is not in the protocol; rather, it comes from the fact that such a miner expends electricity and capital to produce the block and gets no reward).

Casper, on the other hand, works primarily by punishing equivocation - if you send two messages that conflict with each other, then you get very heavily penalized, even if one of those messages aligns with the consensus (read more on this in the blog post on "minimal slashing conditions"). Hence, in the event of a finality reversion attack, those who caused the reversion event are penalized, and everyone else is left untouched; the majority can attack the protocol only at heavy cost, and the majority cannot cause the minority to lose money.It gets more challenging when we move to talking about two other kinds of attacks - liveness faults, and censorship. A liveness fault is one where a large portion of Casper validators go offline, preventing the consensus from reaching finality, and a censorship fault is one where a majority of Casper validators refuse to accept some transactions, or refuse to accept consensus messages from other Casper validators (the victims) in order to deprive them of rewards.

This touches on a fundamental dichotomy: speaker/listener fault equivalence.

Suppose that person B says that they did not receive a message from person A. There are two possible explanations: (i) person A did not send the message, (ii) person B pretended not to hear the message. Given just the evidence of B's claim, there is no way to tell which of the two explanations is correct. The relation to blockchain protocol incentivization is this: if you see a protocol execution where 70% of validators' messages are included in the chain and 30% are not, and see nothing else (and this is what the blockchain sees), then there is no way to tell whether the problem is that 30% are offline or 70% are censoring. If we want to make both kinds of attacks expensive, there is only one thing that we can do: penalize both sides.

Penalizing both sides allows either side to "grief" the other, by going offline if they are a minority and censoring if they are a majority. However, we can establish bounds on how easy this griefing is, through the technique of griefing factor analysis. The griefing factor of a strategy is essentially the amount of money lost by the victims divided by the amount of money lost by the attackers, and the griefing factor of a protocol is the highest griefing factor that it allows. For example, if a protocol allows me to cause you to lose $3 at a cost of $1 to myself, then the griefing factor is 3. If there are no ways to cause others to lose money, the griefing factor is zero, and if you can cause others to lose money at no cost to yourself (or at a benefit to yourself), the griefing factor is infinity.

In general, wherever a speaker/listener dichotomy exists, the griefing factor cannot be globally bounded above by any value below 1. The reason is simple: either side can grief the other, so if side \(A\) can grief side \(B\) with a factor of \(x\) then side \(B\) can grief side \(A\) with a factor of \(\frac{1}{x}\); \(x\) and \(\frac{1}{x}\) cannot both be below 1 simultaneously. We can play around with the factors; for example, it may be considered okay to allow griefing factors of 2 for majority attackers in exchange for keeping the griefing factor at 0.5 for minorities, with the reasoning that minority attackers are more likely. We can also allow griefing factors of 1 for small-scale attacks, but specifically for large-scale attacks force a chain split where on one chain one side is penalized and on another chain another side is penalized, trusting the market to pick the chain where attackers are not favored. Hence there is a lot of room for compromise and making tradeoffs between different concerns within this framework.

Penalizing both sides has another benefit: it ensures that if the protocol is harmed, the attacker is penalized. This ensures that whoever the attacker is, they have an incentive to avoid attacking that is commensurate with the amount of harm done to the protocol. However, if we want to bound the ratio of harm to the protocol over cost to attackers, we need a formalized way of measuring how much harm to the protocol was done.

This introduces the concept of the protocol utility function - a formula that tells us how well the protocol is doing, that should ideally be calculable from inside the blockchain. In the case of a proof of work chain, this could be the percentage of all blocks produced that are in the main chain. In Casper, protocol utility is zero for a perfect execution where every epoch is finalized and no safety failures ever take place, with some penalty for every epoch that is not finalized, and a very large penalty for every safety failure. If a protocol utility function can be formalized, then penalties for faults can be set as close to the loss of protocol utility resulting from those faults as possible.