Engineering Security Through Coordination Problems

2017 May 08

See all posts

Engineering Security Through Coordination Problems

Recently, there was a small spat between the Core and Unlimited

factions of the Bitcoin community, a spat which represents perhaps the

fiftieth time the same theme was debated, but which is nonetheless

interesting because of how it highlights a very subtle philosophical

point about how blockchains work.

ViaBTC, a mining pool that favors Unlimited, tweeted "hashpower is

law", a usual talking point for the Unlimited side, which believes that

miners have, and should have, a very large role in the governance of

Bitcoin, the usual argument for this being that miners are the one

category of users that has a large and illiquid financial incentive in

Bitcoin's success. Greg Maxwell (from the Core side) replied

that "Bitcoin's security works precisely because hash power is NOT

law".

The Core argument is that miners only have a limited role in the Bitcoin

system, to secure the ordering of transactions, and they should NOT have

the power to determine anything else, including block size limits and

other block validity rules. These constraints are enforced by full nodes

run by users - if miners start producing blocks according to a set of

rules different than the rules that users' nodes enforce, then the

users' nodes will simply reject the blocks, regardless of whether 10% or

60% or 99% of the hashpower is behind them. To this, Unlimited often

replies with something like "if 90% of the hashpower is behind a new

chain that increases the block limit, and the old chain with 10%

hashpower is now ten times slower for five months until difficulty

readjusts, would you

really not update your client to accept

the new chain?"

Many people often argue

against

the use of public blockchains for applications that involve real-world

assets or anything with counterparty risk. The critiques are either

total, saying that there is no point in implementing such use cases on

public blockchains, or partial, saying that while there may be

advantages to storing the data on a public chain, the

business logic should be executed off chain.

The argument usually used is that in such applications, points of trust

exist already - there is someone who owns the physical assets that back

the on-chain permissioned assets, and that someone could always choose

to run away with the assets or be compelled to freeze them by a

government or bank, and so managing the digital representations of these

assets on a blockchain is like paying for a reinforced steel door for

one's house when the window is open. Instead, such systems should use

private chains, or even traditional server-based solutions, perhaps

adding bits and pieces of cryptography to improve auditability, and

thereby save on the inefficiencies and costs of putting everything on a

blockchain.

The arguments above are both flawed in their pure forms, and

they are flawed in a similar way. While it is theoretically

possible for miners to switch 99% of their hashpower to a chain

with new rules (to make an example where this is uncontroversially bad,

suppose that they are increasing the block reward), and even spawn-camp

the old chain to make it permanently useless, and it is also

theoretically possible for a centralized manager of an asset-backed

currency to cease honoring one digital token, make a new digital token

with the same balances as the old token except with one particular

account's balance reduced to zero, and start honoring the new token, in

practice those things are both quite hard to do.

In the first case, users will have to realize that something is wrong

with the existing chain, agree that they should go to the new chain that

the miners are now mining on, and download the software that accepts the

new rules. In the second case, all clients and applications that depend

on the original digital token will break, users will need to update

their clients to switch to the new digital token, and smart contracts

with no capacity to look to the outside world and see that they need to

update will break entirely. In the middle of all this, opponents of the

switch can create a fear-uncertainty-and-doubt campaign to try to

convince people that maybe they shouldn't update their clients after

all, or update their client to some third set of rules (eg.

changing proof of work), and this makes implementing the switch even

more difficult.

Hence, we can say that in both cases, even though there theoretically

are centralized or quasi-centralized parties that could force a

transition from state A to state B, where state B is disagreeable to

users but preferable to the centralized parties, doing so requires

breaking through a hard coordination problem.

Coordination problems are everywhere in society and are often a bad

thing - while it would be better for most people if the English language

got rid of its highly complex and irregular spelling system and made a

phonetic one, or if the United States switched to metric, or if we could

immediately drop all

prices and wages by ten percent in the event of a recession, in

practice this requires everyone to agree on the switch at the same time,

and this is often very very hard.

With blockchain applications, however, we are doing something

different: we are using coordination problems to our

advantage, using the friction that coordination problems create

as a bulwark against malfeasance by centralized actors. We can build

systems that have property X, and we can guarantee that they will

preserve property X to a high degree because changing the rules from X

to not-X would require a whole bunch of people to agree to update their

software at the same time. Even if there is an actor that could force

the change, doing so would be hard. This is the kind of security that

you gain from client-side validation of blockchain consensus rules.

Note that this kind of security relies on the decentralization of users

specifically. Even if there is only one miner in the world, there is

still a difference between a cryptocurrency mined by that miner and a

PayPal-like centralized system. In the latter case, the operator can

choose to arbitrarily change the rules, freeze people's money, offer bad

service, jack up their fees or do a whole host of other things, and the

coordination problems are in the operator's favor, as such systems have

substantial network effects and so very many users would have to agree

at the same time to switch to a better system. In the former case,

client-side validation means that many attempts at mischief that the

miner might want to engage in are by default rejected, and the

coordination problem now works in the users' favor.

Note that the arguments above do NOT, by themselves,

imply that it is a bad idea for miners to be the principal actors

coordinating and deciding the block size (or in Ethereum's case, the gas

limit). It may well be the case that, in the specific case of the

block size/gas limit, "government by coordinated miners with

aligned incentives" is the optimal approach for deciding this one

particular policy parameter, perhaps because the risk of miners abusing

their power is lower than the risk that any specific chosen hard limit

will prove wildly inappropriate for market conditions a decade after the

limit is set. However, there is nothing unreasonable about saying that

government-by-miners is the best way to decide one policy parameter, and

at the same saying that for other parameters (eg. block reward)

we want to rely on client-side validation to ensure that miners are

constrained. This is the essence of engineering decentralized

instutitions: it is about strategically using coordination problems to

ensure that systems continue to satisfy certain desired properties.

The arguments above also do not imply that it is always optimal to try

to put everything onto a blockchain even for services that are

trust-requiring. There generally are at least some gains to be made by

running more business logic on a blockchain, but they are often much

smaller than the losses to efficiency or privacy. And this ok; the

blockchain is not the best tool for every task. What the arguments above

do imply, though, is that if you are building a

blockchain-based application that contains many centralized components

out of necessity, then you can make substantial further gains in

trust-minimization by giving users a way to access your application

through a regular blockchain client (eg. in the case of Ethereum, this

might be Mist, Parity, Metamask or Status), instead of getting them to

use a web interface that you personally control.

Theoretically, the benefits of user-side validation are

optimized if literally every user runs an independent "ideal full node"

- a node that accepts all blocks that follow the protocol rules that

everyone agreed to when creating the system, and rejects all blocks that

do not. In practice, however, this involves asking every user to process

every transaction run by everyone in the network, which is clearly

untenable, especially keeping in mind the rapid growth of smartphone

users in the developing world.

There are two ways out here. The first is that we can realize that

while it is optimal from the point of view of the above

arguments that everyone runs a full node, it is certainly not

required. Arguably, any major blockchain running at full

capacity will have already reached the point where it will not make

sense for "the common people" to expend a fifth of their hard drive

space to run a full node, and so the remaining users are hobbyists and

businesses. As long as there is a fairly large number of them, and they

come from diverse backgrounds, the coordination problem of getting these

users to collude will still be very hard.

Second, we can rely on strong light client

technology.

There are two levels of "light clients" that are generally possible

in blockchain systems. The first, weaker, kind of light client simply

convinces the user, with some degree of economic assurance, that they

are on the chain that is supported by the majority of the network. This

can be done much more cheaply than verifying the entire chain, as all

clients need to do is in proof of work schemes verify nonces or in proof

stake schemes verify signed certificates that state "either the root

hash of the state is what I say it is, or you can publish this

certificate into the main chain to delete a large amount of my money".

Once the light client verifies a root hash, they can use Merkle trees to

verify any specific piece of data that they might want to verify.

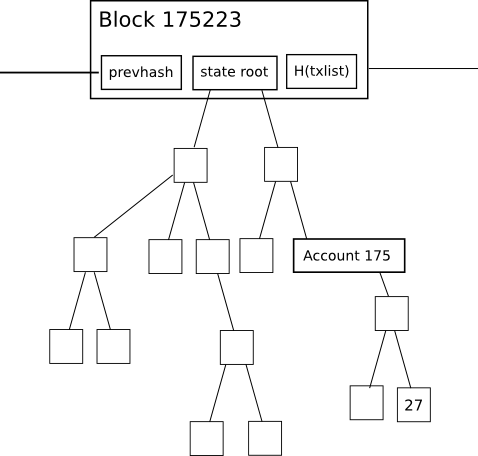

Look, it's a Merkle tree!

The second level is a "nearly fully verifying" light client. This

kind of client doesn't just try to follow the chain that the majority

follows; rather, it also tries to follow only chains that follow all the

rules. This is done by a combination of strategies; the simplest to

explain is that a light client can work together with specialized nodes

(credit to Gavin Wood for coming up with the name "fishermen") whose

purpose is to look for blocks that are invalid and generate "fraud

proofs", short messages that essentially say "Look! This block has a

flaw over here!". Light clients can then verify that specific part of a

block and check if it's actually invalid.

If a block is found to be invalid, it is discarded; if a light client

does not hear any fraud proofs for a given block for a few minutes, then

it assumes that the block is probably legitimate. There's a bit

more complexity involved in handling the case where the problem is

not data that is bad, but rather data that is missing,

but in general it is possible to get quite close to catching all

possible ways that miners or validators can violate the rules of the

protocol.

Note that in order for a light client to be able to efficiently

validate a set of application rules, those rules must be executed inside

of consensus - that is, they must be either part of the protocol or part

of a mechanism executing inside the protocol (like a smart contract).

This is a key argument in favor of using the blockchain for both data

storage and business logic execution, as opposed to just data

storage.

These light client techniques are imperfect, in that they do rely on

assumptions about network connectivity and the number of other light

clients and fishermen that are in the network. But it is actually not

crucial for them to work 100% of the time for 100% of validators.

Rather, all that we want is to create a situation where any attempt by a

hostile cartel of miners/validators to push invalid blocks without user

consent will cause a large amount of headaches for lots of people and

ultimately require everyone to update their software if they want to

continue to synchronize with the invalid chain. As long as this is

satisfied, we have achieved the goal of security through coordination

frictions.

Engineering Security Through Coordination Problems

2017 May 08 See all postsRecently, there was a small spat between the Core and Unlimited factions of the Bitcoin community, a spat which represents perhaps the fiftieth time the same theme was debated, but which is nonetheless interesting because of how it highlights a very subtle philosophical point about how blockchains work.

ViaBTC, a mining pool that favors Unlimited, tweeted "hashpower is law", a usual talking point for the Unlimited side, which believes that miners have, and should have, a very large role in the governance of Bitcoin, the usual argument for this being that miners are the one category of users that has a large and illiquid financial incentive in Bitcoin's success. Greg Maxwell (from the Core side) replied that "Bitcoin's security works precisely because hash power is NOT law".

The Core argument is that miners only have a limited role in the Bitcoin system, to secure the ordering of transactions, and they should NOT have the power to determine anything else, including block size limits and other block validity rules. These constraints are enforced by full nodes run by users - if miners start producing blocks according to a set of rules different than the rules that users' nodes enforce, then the users' nodes will simply reject the blocks, regardless of whether 10% or 60% or 99% of the hashpower is behind them. To this, Unlimited often replies with something like "if 90% of the hashpower is behind a new chain that increases the block limit, and the old chain with 10% hashpower is now ten times slower for five months until difficulty readjusts, would you really not update your client to accept the new chain?"

The argument usually used is that in such applications, points of trust exist already - there is someone who owns the physical assets that back the on-chain permissioned assets, and that someone could always choose to run away with the assets or be compelled to freeze them by a government or bank, and so managing the digital representations of these assets on a blockchain is like paying for a reinforced steel door for one's house when the window is open. Instead, such systems should use private chains, or even traditional server-based solutions, perhaps adding bits and pieces of cryptography to improve auditability, and thereby save on the inefficiencies and costs of putting everything on a blockchain.Many people often argue against the use of public blockchains for applications that involve real-world assets or anything with counterparty risk. The critiques are either total, saying that there is no point in implementing such use cases on public blockchains, or partial, saying that while there may be advantages to storing the data on a public chain, the business logic should be executed off chain.

The arguments above are both flawed in their pure forms, and they are flawed in a similar way. While it is theoretically possible for miners to switch 99% of their hashpower to a chain with new rules (to make an example where this is uncontroversially bad, suppose that they are increasing the block reward), and even spawn-camp the old chain to make it permanently useless, and it is also theoretically possible for a centralized manager of an asset-backed currency to cease honoring one digital token, make a new digital token with the same balances as the old token except with one particular account's balance reduced to zero, and start honoring the new token, in practice those things are both quite hard to do.

In the first case, users will have to realize that something is wrong with the existing chain, agree that they should go to the new chain that the miners are now mining on, and download the software that accepts the new rules. In the second case, all clients and applications that depend on the original digital token will break, users will need to update their clients to switch to the new digital token, and smart contracts with no capacity to look to the outside world and see that they need to update will break entirely. In the middle of all this, opponents of the switch can create a fear-uncertainty-and-doubt campaign to try to convince people that maybe they shouldn't update their clients after all, or update their client to some third set of rules (eg. changing proof of work), and this makes implementing the switch even more difficult.

Hence, we can say that in both cases, even though there theoretically are centralized or quasi-centralized parties that could force a transition from state A to state B, where state B is disagreeable to users but preferable to the centralized parties, doing so requires breaking through a hard coordination problem. Coordination problems are everywhere in society and are often a bad thing - while it would be better for most people if the English language got rid of its highly complex and irregular spelling system and made a phonetic one, or if the United States switched to metric, or if we could immediately drop all prices and wages by ten percent in the event of a recession, in practice this requires everyone to agree on the switch at the same time, and this is often very very hard.

With blockchain applications, however, we are doing something different: we are using coordination problems to our advantage, using the friction that coordination problems create as a bulwark against malfeasance by centralized actors. We can build systems that have property X, and we can guarantee that they will preserve property X to a high degree because changing the rules from X to not-X would require a whole bunch of people to agree to update their software at the same time. Even if there is an actor that could force the change, doing so would be hard. This is the kind of security that you gain from client-side validation of blockchain consensus rules.

Note that this kind of security relies on the decentralization of users specifically. Even if there is only one miner in the world, there is still a difference between a cryptocurrency mined by that miner and a PayPal-like centralized system. In the latter case, the operator can choose to arbitrarily change the rules, freeze people's money, offer bad service, jack up their fees or do a whole host of other things, and the coordination problems are in the operator's favor, as such systems have substantial network effects and so very many users would have to agree at the same time to switch to a better system. In the former case, client-side validation means that many attempts at mischief that the miner might want to engage in are by default rejected, and the coordination problem now works in the users' favor.

The arguments above also do not imply that it is always optimal to try to put everything onto a blockchain even for services that are trust-requiring. There generally are at least some gains to be made by running more business logic on a blockchain, but they are often much smaller than the losses to efficiency or privacy. And this ok; the blockchain is not the best tool for every task. What the arguments above do imply, though, is that if you are building a blockchain-based application that contains many centralized components out of necessity, then you can make substantial further gains in trust-minimization by giving users a way to access your application through a regular blockchain client (eg. in the case of Ethereum, this might be Mist, Parity, Metamask or Status), instead of getting them to use a web interface that you personally control.Note that the arguments above do NOT, by themselves, imply that it is a bad idea for miners to be the principal actors coordinating and deciding the block size (or in Ethereum's case, the gas limit). It may well be the case that, in the specific case of the block size/gas limit, "government by coordinated miners with aligned incentives" is the optimal approach for deciding this one particular policy parameter, perhaps because the risk of miners abusing their power is lower than the risk that any specific chosen hard limit will prove wildly inappropriate for market conditions a decade after the limit is set. However, there is nothing unreasonable about saying that government-by-miners is the best way to decide one policy parameter, and at the same saying that for other parameters (eg. block reward) we want to rely on client-side validation to ensure that miners are constrained. This is the essence of engineering decentralized instutitions: it is about strategically using coordination problems to ensure that systems continue to satisfy certain desired properties.

Theoretically, the benefits of user-side validation are optimized if literally every user runs an independent "ideal full node" - a node that accepts all blocks that follow the protocol rules that everyone agreed to when creating the system, and rejects all blocks that do not. In practice, however, this involves asking every user to process every transaction run by everyone in the network, which is clearly untenable, especially keeping in mind the rapid growth of smartphone users in the developing world.

There are two ways out here. The first is that we can realize that while it is optimal from the point of view of the above arguments that everyone runs a full node, it is certainly not required. Arguably, any major blockchain running at full capacity will have already reached the point where it will not make sense for "the common people" to expend a fifth of their hard drive space to run a full node, and so the remaining users are hobbyists and businesses. As long as there is a fairly large number of them, and they come from diverse backgrounds, the coordination problem of getting these users to collude will still be very hard.

Second, we can rely on strong light client technology.

There are two levels of "light clients" that are generally possible in blockchain systems. The first, weaker, kind of light client simply convinces the user, with some degree of economic assurance, that they are on the chain that is supported by the majority of the network. This can be done much more cheaply than verifying the entire chain, as all clients need to do is in proof of work schemes verify nonces or in proof stake schemes verify signed certificates that state "either the root hash of the state is what I say it is, or you can publish this certificate into the main chain to delete a large amount of my money". Once the light client verifies a root hash, they can use Merkle trees to verify any specific piece of data that they might want to verify.

Look, it's a Merkle tree!

The second level is a "nearly fully verifying" light client. This kind of client doesn't just try to follow the chain that the majority follows; rather, it also tries to follow only chains that follow all the rules. This is done by a combination of strategies; the simplest to explain is that a light client can work together with specialized nodes (credit to Gavin Wood for coming up with the name "fishermen") whose purpose is to look for blocks that are invalid and generate "fraud proofs", short messages that essentially say "Look! This block has a flaw over here!". Light clients can then verify that specific part of a block and check if it's actually invalid.

If a block is found to be invalid, it is discarded; if a light client does not hear any fraud proofs for a given block for a few minutes, then it assumes that the block is probably legitimate. There's a bit more complexity involved in handling the case where the problem is not data that is bad, but rather data that is missing, but in general it is possible to get quite close to catching all possible ways that miners or validators can violate the rules of the protocol.

Note that in order for a light client to be able to efficiently validate a set of application rules, those rules must be executed inside of consensus - that is, they must be either part of the protocol or part of a mechanism executing inside the protocol (like a smart contract). This is a key argument in favor of using the blockchain for both data storage and business logic execution, as opposed to just data storage.

These light client techniques are imperfect, in that they do rely on assumptions about network connectivity and the number of other light clients and fishermen that are in the network. But it is actually not crucial for them to work 100% of the time for 100% of validators. Rather, all that we want is to create a situation where any attempt by a hostile cartel of miners/validators to push invalid blocks without user consent will cause a large amount of headaches for lots of people and ultimately require everyone to update their software if they want to continue to synchronize with the invalid chain. As long as this is satisfied, we have achieved the goal of security through coordination frictions.